The History of the 2nd Amendment: A Collective or Individual Right? - Part 2

A three-part series analyzing and refuting historical evidence produced by gun rights activist Kostas Moros on the right to "bear arms"

By: Dru Stevenson

This is Part 2 of a three-part series. Part 1 looked into how much, or even if, the Founders settled on an individual or personal right to own guns while drafting the Second Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Today, Dru Stevenson takes an exhaustive dive into the 19th century legal treatises and political speeches that pro-gun lawyer, Kostas Moros, cites to try to prove his modern “individual rights” interpretation.

Kostas Moros’ Sources

William Rawle, 1868

Moros first cites a legal treatise by William Rawle, A View of the Constitution of the United States, excerpted below.

Note that Rawle’s treatise, though published in 1868, was not cited by any federal court until 1963, a century later, and almost all federal court citations to it came after 2001. It was cited only twice by state courts in the 1800’s, and then not again until 2004. Law review articles did not cite Rawle’s discussion of the Second Amendment until the 1990’s; and before that, on unrelated constitutional issues, legal authors cited it three times in the 1940’s, and then not again until the 1970’s.

In other words, the text does not seem to have been influential on the courts or legal experts until the NRA started aggressively promoting the “individual right” interpretation in the modern era.

There is no reason to think Rawle’s thinking about the Second Amendment was representative of the prevailing view in his own generation. He doesn’t even support his own statements about the Second Amendment with citations to court decisions from back then. Plenty of legal authors in the 1800’s espoused idiosyncratic or unpopular views on specific issues like states’ rights, the powers of the legislature, and so forth.

Moros seems to think this one excerpt proves his point that the Second Amendment protected an individual right to own guns separate from being a member of the militia. This is not clear at all from the excerpt itself. It begins by saying that, at the least, the 2A prohibits Congress from “disarming the people.” This sounds like a complete disarmament of the populace, not disarming certain individuals or restricting what types of guns or how many guns individuals can own. Moreover, it is equally compatible with the interpretation that the 2A prohibits Congress from disbanding and disarming the state militias.

Rawle then proceeds to concede that a state might try to dissolve its militia and disarm the entire populace. The Bill of Rights originally applied only to the federal government, so it was unclear that it would prohibit a state from doing this, but Rawle suggests that someone could appeal to the Second Amendment to try to stop a state from doing so. Rawle then summarizes some of the history of gun restrictions in England.

I think all of this could equally support the collective right view (militias), so I don’t think it is strong evidence for the idea that an individual had a constitutional right to own weapons for personal self-defense. Note that the excerpt from Rawle cuts off talking about suppressing popular insurrections (like Shay’s Rebellion in Massachusetts, which many historians consider to be the event that prompted the Constitutional Convention). Putting down insurrections by factions of political fanatics or slave revolts was, in fact, the primary function of the state militias.

Moros then quotes another page of Rawle that explained that private militias or armed groups could be prohibited notwithstanding the Second Amendment (groups like today’s Oath Keepers or Proud Boys), and that even individuals carrying weapons could be forced to give a good reason for doing so. Kostas says this is merely a prohibition on carrying arms with the intention of committing crimes, but that is not what it says. Instead, it says that if there is any reason to be concerned that someone “purposes” to use their weapons for crimes, they can be forced to post a surety (bond), and can be imprisoned for refusing to do so. It does not say, as Moros suggests it says, that individuals can carry any arms they want wherever they want as long as they have good intentions. He infers that, but the text itself merely says that requiring surety bonds for public carrying is permissible under the Second Amendment.

Joel Prentiss Bishop, 1868

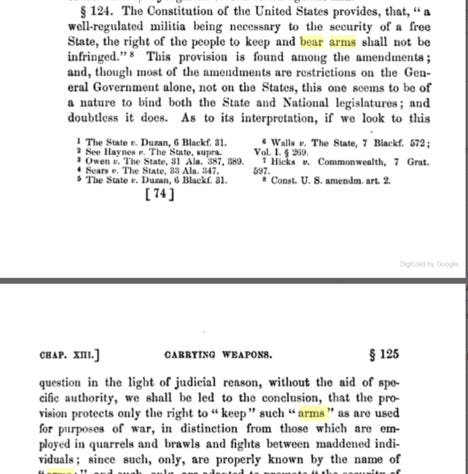

The next excerpt is this one, below, from Joel Bishop, published almost 80 years after the Bill of Rights was ratified.

Moros says, “the 2A *only* protects weapons of war. In other words, Bishop would believe they can ban your brass knuckles or pocket pistols, but not your M16!” I truly do not see why he would think this passage supports his view that the Second Amendment was not about militia service, when it says it was only for weapons of “war” and not for the types of weapons “which are employed in quarrels and brawls and fights between maddened individuals.”

In other words, weapons useful for personal self-defense, like handguns, are not covered under the Second Amendment. This quote seems to support the exact opposite view from the “individual right to bear arms for self defense.” The “weapons of war” were not carried about for personal self-defense. They were too heavy, expensive, and cumbersome. Men possessed them for when the citizen militia was summoned.

Joel Prentiss Bishop’s treatise on Criminal Law was cited by only one federal court in the 1800’s, and then not again until 1967. It was cited a fair amount by state courts in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, but not on the meaning of the right to bear arms, but rather pertaining to his discussion of other crimes. No state or federal court has ever cited this passage from Bishop about the right to bear arms, which is unsurprising, because it does not really support the views of gun rights advocates. Bishop was not cited by law review authors until the twentieth century, and then only about once a decade until the 1980’s. This passage about the right to bear arms was not cited by any law review until 2009.

I don’t think Bishop’s statements support the “individual right” view at all. In any case, there is no evidence that his writing about the Second Amendment had any influence on the courts or legal scholars before gun rights advocates started citing him after Heller.

Robert Desty, 1881

Moros then cites Desty:

Again, I don’t think this supports the “individual rights” view as much as Moros suggests it does.

First, it says it applies only to the federal government not to the states, and expressly allows states to enact gun control laws, such as a complete prohibition on concealed carrying of guns. It does say that states cannot ban “openly bearing arms,” but it’s not clear this is referring to an individual right versus service in the militia. Notice, it doesn’t say “openly carrying arms” – “openly bearing arms” had the connotation of brandishing or using the weapons in battle.

It then says that the purpose was to prevent the “oppression and enslavement” of the people (that is, the entire population) if the entire populace was disarmed. This last sentence is more supportive of a collective right view than an individual right view.

The concern is about disarming the entire populace and disbanding the militia, not about protecting each individual’s right to be armed for personal self-defense against criminals.

Note that even though courts have cited Desty on other legal points over the years, no court (state or federal) has ever cited him in connection with the Second Amendment or the right to bear arms, nor have law review authors.

Garrett Davis

Then Moros cites a speech by Kentucky Senator Garrett Davis on the eve of the Civil War, complaining about the tyranny of the President of the United States and the martial law-type actions taken, in violation of a litany of rights.

The right to keep and bear arms is mentioned only in passing, and it is simply not clear that this supports an “individual right” to bear arms for personal self-defense, versus a collective or militia right (the Union soldiers accusing people of sedition in military tribunals seems to fit better with the latter). There is no reason to think that a politician’s speech reflected the prevailing views of the legal community or the general public, or that this excerpt had any influence on courts or legal theorists at the time. Davis was a Unionist elected to fill a seat vacated by the expulsion of a Confederate senator from his state.

Henry Campbell Black

It is rather confusing that Moros would cite this excerpt, which seems to support the opposite of his views on most issues:

Just to be clear, Black says, 1) the 2A applies only to the federal government, and does not restrict the states from passing gun regulations; 2) he really seems to be talking about the state citizen militia, not an individual right to bear arms. Note he says, “the state legislatures may enact laws to control and regulate all military organizations, and the drilling and parading of military bodies and organizations…,” and that the “right” is to keep “arms of modern warfare” (as opposed to arms for personal self-defense or hunting).

Black explicitly states that the Second Amendment does not apply to “weapons used in fights, brawls, and riots” or the “instruments of private feuds or vengeance.” This would certainly included handguns and pistols. He further says it is permissible for states to ban concealed carrying of firearms.

I don’t understand why Moros thinks this supports his view about the individual right to bear arms for self-defense. This excerpt is more supportive of the collective-militia view.

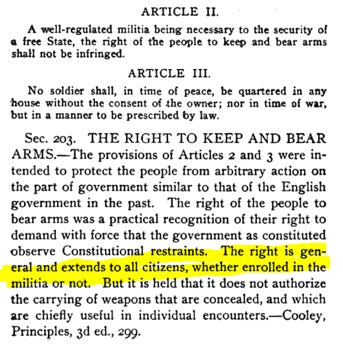

Thomas Cooley, 1898

Moros’ next source is Thomas Cooley, writing in 1898 (too late for the Supreme Court to consider relevant for the meaning of the Second Amendment, according to its 2022 opinion in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen).

Once again, this is talking about the collective right (citizen militia), not an individual right to arm oneself for personal self-defense.

Cooley says the Second Amendment is based on the 1688 English Bill of Rights, which was in response to a tumultuous period of bloody regime changes and dynasty downfalls – Protestant to Catholic and back to Protestant again. Each new monarch had to deal with a large segment of the population that favored the one just overthrown, and they would undertake efforts to disarm entire segments of the populace (like Catholics or Protestants). This was not about ensuring individuals could shoot a burglar in their own home.

Moros says, “Cooley not only addressed but ultimately dismissed the suggestion the amendment protected only a ‘militia right,’” and he provides this quote as proof:

“It may be supposed from the phraseology of this provision that the right to keep and bear arms was only guaranteed to the militia; but this would be an interpretation not warranted by the intent[…]. The meaning of the provision undoubtedly is, that the people, from whom the militia must be taken, shall have the right to keep and bear arms, and they need no permission or regulation of law for the purpose.”

But Moros omitted a crucial section in the middle. Here’s the full quote:

“It may be supposed from the phraseology of this provision that the right to keep and bear arms was only guaranteed to the militia; but this would be an interpretation not warranted by the intent. The militia, as has been explained elsewhere, consists of those persons who, under the laws, are liable to the performance of military duty, and are officered and enrolled for service when called upon. But the law makes provision for the enrollment of all who are fit to perform military duty, or of a small number only, or it may wholly omit to make any provision at all; and if the right were limited to those enrolled, the purpose of the guarantee might be defeated altogether by the action or the neglect to act of the government it was meant to hold in check. The meaning of the provision undoubtedly is, that the people, from whom the militia must be taken, shall have the right to keep and bear arms, and they need no permission or regulation of law for the purpose. But this enables the government to have a well-regulated militia; for to bear arms implies something more than mere keeping; it implies the learning to handle and use them in a way that makes those who keep them ready for their efficient use; in other words, it implies the right to meet for voluntary discipline in arms, observing in so doing the laws of public order.”

This is talking about the collective right, citizen militias – but is merely saying the right to keep and bear arms does not apply only to those on active duty, because those waiting to be called up need to be able to train and practice.

There is nothing here about an individual right to arm oneself solely for personal self-defense. Cooley is clearly talking about citizens who are eligible for militia service, even if they have not been called up yet.

Rep. Edward Wade, 1856

Kostas then gives another speech from a politician in Congress, where the Congressman claims that the right to bear arms has been taken away from settlers in Kansas, during the “Bleeding Kansas” era.

This speech is about “Beecher’s Bibles,” not about an individual right to bear arms to defend oneself against crimes like assault or robbery. Northern abolitionists were shipping rifles to abolitionist settlers in Kansas Territory, and federal and state authorities responded to the outbreaks of violence by forbidding the import of firearms into the Territory. Henry Ward Beecher and others began smuggling them in crates covered with Bibles.

Wade’s speech was about the federal response to the open, armed conflict between pro-slavery settlers and abolitionists in Kansas. Wade was calling for the exercise of the collective right (groups of citizens to take up arms against what they perceived as an illegitimate government), not about an individual right to own guns for personal self-defense. Those being deprived of arms were not defending themselves against crimes. They were abolitionists resorting to violence to end slavery. Wade was an abolitionist.

Moros then cites a summary from the Congressional debates about the 14th Amendment and concern about freed slaves in the Southern states not having arms to defend themselves against lynch mobs, the KKK, etc. The topic of what various members in Congress believed after the Civil War is a big topic, hotly debated by historians for sure, but not that relevant to what the Second Amendment meant to its drafters or the generation that ratified it.

The Reconstruction Era presented completely different social and political issues, and very different attitudes about which groups could use violence to enforce the new federal agenda.

John Norton Pomeroy, 1888

Kostas then quotes an 1888 legal treatise by John Norton Pomeroy (again, too late to be relevant for understanding the original meaning of the Second Amendment, according to the Supreme Court in Bruen). This is very similar to the quote by Cooley above, but Moros thinks it supports the individual right to bear arms for self-defense, separate from the militia or collective right:

“John Norton Pomeroy, another major legal scholar of the 19th century, best explained the view that securing a well-armed militia is not mutually exclusive with an individual right but is instead wholly dependent on it. In his 1888 book, An Introduction to the Constitutional Law of the United States, Pomeroy wrote that ‘The object of this clause is to secure a well-armed militia[…].’ But a militia would be useless unless the citizens were enabled to exercise themselves in the use of warlike weapons. To preserve this privilege, and to secure the people the ability to oppose themselves in military force against the usurpations of government, as well as against enemies from without, that government is forbidden by any law or proceeding to invade or destroy the right to keep and bear arms.”

However, Pomeroy added that restricting concealed weapons or barring individuals from accumulating “quantities of arms with the design to use them in a riotous or seditious manner” was acceptable.

He concluded that the Second Amendment “is analogous to the one securing freedom of speech and of the press. Freedom, not license, is secured; the fair use, not the libelous abuse, is protected.”

As seen from the discussion above, “warlike weapons” were not the same as the weapons an individual would normally carry for personal self-defense, or use to defend one’s home against an intruder. These were battlefield weapons.

Pomeroy ties the “right to bear arms” directly to the militia, saying that it’s necessary for those eligible for militia service to have a battlefield weapon on hand “to oppose themselves in military force against the usurpations of government” (emphasis added) and against “enemies without” (foreign invading armies). Pomeroy then goes on to say that the government can restrict the number of weapons an individual owns or the right to concealed carry.

I truly don’t understand why Moros thinks this quote supports his side. Pomeroy explicitly links the right to being ready to participate in the militia, and makes no mention of personal self-defense.

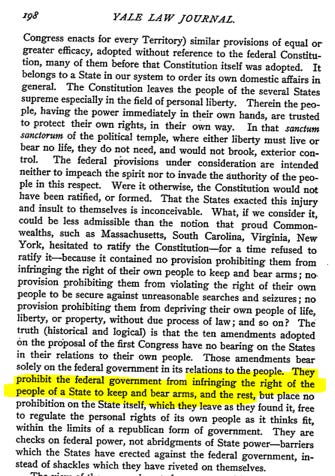

Yale Law Journal, 1900

Moros then quotes a Yale Law Journal article from 1900 (too late to be relevant according to the Supreme Court in Bruen). Again, this is not clear that it is talking about an individual right to own guns for personal self-defense versus a collective right.

I concede that the following sentence, taken out of context, sounds more like an individual right, though not indisputably so: “Therein people, having the power immediately in their own hands, are entrusted to protect their own rights, in their own way.” But the writer then goes on to talk about how the Second Amendment applies only to the federal government and does not limit the states’ power to restrict these rights.

The article overall is about the Constitutional status of territories, not about the parameters of the right to bear arms. So even though the sentence above sounds sort of like an individual right to own guns, the writer immediately suggests that states can limit that right (of individuals to own guns) without violating the Second Amendment.

As a side note, this article, which was published more than a century after the Bill of Rights, was never cited by a court until 2011, and was not cited by any other law review articles until 1984.

Adam Seybert, 1818

“Adam Seybert, a doctor who served in Congress from 1809 to 1815,” Moros explains, “wrote a book in 1818 whose title was quite the mouthful: Statistical Annals: Embracing Views of the Population, Commerce, Navigation, Fisheries, Public Lands, Post-Office, Establishment, Revenues, Mint, Military and Naval Establishments, Expenditures, Public Debt and Sinking Fund of the United States of America.

“Yet, as comically lengthy as his title was, Dr. Seybert’s view on the Second Amendment was concise and to the point. Dr. Seybert explained that ‘our constitution guarantees to every citizen the right ‘to keep and bear arms,’ while in other countries this very important trust is controlled by the caprice and tyranny of an individual.’

“Dr. Seybert was not alone, and others went even further to talk about how the right the Second Amendment protects applies not just to defense against tyranny or foreign invasion but also personal defense.”

Once again, Moros has taken a passage that is expressly talking about “the military population of the United States” and connecting the Second Amendment to the citizen preparedness for military/militia service. This is the essence of the “collective right” view, not an individual right to have a gun for shooting burglars or muggers.

Read the full excerpt below.

Benjamin Vaughan Abbott, 1879

Moros then gives an excerpt from Abbott, published in 1879 (probably too late for the the Supreme Court to consider it relevant under Bruen, but unclear). Moros says, “It notes that the dispute in the caselaw was about what arms are included. No mention of lack of an individual right.”

First, this is a typical logical fallacy, claiming that the absence of evidence is evidence of absence. The fact that it does not mention an individual right is just as likely to indicate that nobody thought there was such a thing, as opposed to everyone took it for granted. Check out the actual quote:

Note that this states, “The constitutional right to keep and bear arms does not extend to carrying bowie knives, firearms, etc. State v. Reid, 1 Ala. 612. The constitutional provision means such weapons as are used for purposes of war, and does not include weapons not used in civilian warfare: small pistols, for example.”

Contrary to what Moros says, this actually does sound like there is no individual right to keep and bear arms. It says the Second Amendment doesn’t apply to handguns or “carrying firearms.”

Joel Tiffany's Treatise on the Unconstitutionality of American Slavery, 1850

Moros then cites Tiffany’s 1850 book about slavery. The quote is below.

Note that it does not mention firearms anywhere after it quotes the text of the 2A, but is merely talking about the legal right to self-defense. The longstanding legal right to self-defense does not necessarily imply a right to own whatever weapons a person wants just in case they are useful some day for self-defense.

Also notice the chapter heading says, “MILITIA” – but Kostas is citing this for proof that the Second Amendment protected rights unrelated to the militia.

Lysander Spooner - The Unconstitutionality of Slavery, 1856.

This time, Moros quotes an abolitionist anti-slavery book from 1856. I agree with Moros that this says there is an individual right, although the context here is arguing that slaves should be able to have weapons to overpower their slaveholders.

This book was never quoted by law reviews until the 1970’s, so it’s not exactly a source that influenced legal thought in our country. It was never cited by any state or federal court until the Heller decision in 2009.

Also, there is an irony in quoting a book entitled The Unconstitutionality of Slavery to support what the Second Amendment originally meant. Slavery as unconstitutional was definitely not a majority view in the Founding era; and seemingly contradictory to a facial reading of the Constitution, which said that slavery would not be abolished for 25 years. I agree that the quote supports Moros’ view, but I do not agree that it represented the prevailing view in the Founding era, or even in the 1850’s.

David Shephard Garland, James Cockcroft, Lucius Polk McGehee - The American and English Encyclopaedia of Law, 1897

Kostas then quotes a legal encyclopedia from 1897 (again, too late to be relevant for knowing the meaning of the Second Amendment, according to the Supreme Court in Bruen).

Unsurprisingly, it says that the right to keep and bear arms refers not only to “carrying” arms, but also to using arms. Not clear that this affirms there is an individual right to keep and bear arms for personal self-defense versus a collective right, as Moros claims.

Clement Laird Vallandigham, 1863

Moros then provides an excerpts from an 1863 speech of Representative Clement Laird Vallandigham opposing a Civil War-era prohibition on the sale of arms, powder, lead, and percussion caps.

See the discussion above about Congressman Wade. This is a Civil War-era speech about how during the war, the government limited the civilian sale of munitions (arms, lead, powder, percussion caps) because, of course, they were in short supply and needed for the Union Army.

Again, this is a highly specific context, and does not really support the idea that everyone recognized an individual right to bear arms for personal self-defense. This was a political speech in the middle of a war involving people wanting to buy weapons.

If anything, the fact that the federal government thought it could prohibit the sale of firearms and supplies like gunpowder indicates that the majority thought the Second Amendment did not protect against this (courts have long presumed the Constitutionality of statutes).

Moros then includes a blurry image from the Congressional Globe in 1865 (again, during wartime) without comment. I can’t make out enough of what it says to see why he thinks it is important. But it’s another speech from Garrett (see above), not representative of the majority view at the time.

Timothy Farrar - Manual of the Constitution of the United States, 1872

Moros then quotes Farrar’s treatise from 1872:

This is nothing but a passing reference to the “right to keep and bear arms,” without clarifying at all whether it refers to a collective right or an individual right to bear arms for personal self-defense. It supports neither view, but merely makes the obvious and trivially true observation that the Constitution includes the phrase, “right to keep and bear arms.”

George Washington Paschal - The Constitution of the United States Defined and Carefully Annotated, 1868.

Kostas quotes the treatise above:

Once again, this sounds more like the Second Amendment protects against the federal government disarming the entire populace, rather than guaranteeing every individual’s right to have guns for personal self-defense. I don’t think it proves or even supports Moros’ idea of an “individual right.” It’s talking about the populace as a whole, which is the collective right view.

Charles Humphreys, 1822

In his version on The Reload, Kostas quotes Charles Humphreys this way:

“Charles Humphreys shared these views as well. He wrote in his 1822 book, A Compendium of the Common Law in Force in Kentucky To Which is Prefixed a Brief Summary of the Laws of the United States, that, ‘Riding or going armed with dangerous or unusual weapons is a crime against the public peace, by terrifying the people of the land, which is punishable by forfeiture of the arms, and fine and imprisonment. But here it should be remembered, that in this country the constitution guaranties to all persons the right to bear arms; then it can only be a crime to exercise this right in such a manner, as to terrify the people unnecessarily.’”

In his Twitter thread about this, Kostas says, “Always so interesting how even the seemingly pro-restrictions writers still were like, ‘but let’s not go too crazy, because there is an individual right to bear arms.’”

I don’t think it is at all clear that this supports the individual right to bear arms for self-defense versus the collective right (that is, participation in the citizen militia). But if so, he expressly allows for restrictions on public carrying of weapons that Moros claims are unconstitutional.

St. George Tucker, 1803

Moros quotes the familiar passage from St. George Tucker, a Founding-era writer who published a commentary on Blackstone. Here’s Moros’ explanation from The Reload:

“Perhaps the most famous commentary that squares the militia portion of the Second Amendment with the individual-right view came from St. George Tucker, an influential law professor at the College of William & Mary who President James Madison later made a U.S. district judge. He wrote an American version of Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, the first of its kind and a valuable reference work for many American lawyers and law students of the time. Tucker argued in the commentary that, ‘The right of self-defense is the first law of nature: in most governments it has been the study of rulers to confine this right within the narrowest limits possible. Wherever standing armies are kept up, and the right of the people to keep and bear arms is, under any colour or pretext whatsoever, prohibited, liberty, if not already annihilated, is on the brink of destruction.’”

Once again, I don’t think this clearly supports Moros’ interpretation of an individual right to have guns for personal self-defense. The “self-defense” talked about here is the collective right to oppose government tyranny or foreign invasion – note that Tucker says the “right” is prohibited “wherever standing armies are kept up.” This passage is about citizen militias versus a permanent, professional standing army, not about an individual’s right to have guns for shooting burglars or muggers.

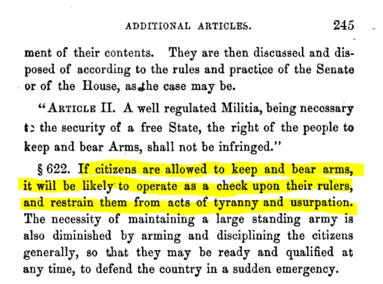

Furman Sheppard, 1855

In his Twitter thread, Moros then quotes from an 1855 book by Furman Sheppard.

This is the “insurrectionist” view of the Second Amendment, that the armed citizenry can keep the government in check. This fits with the collective right view – a well-trained citizen militia could resist armed governmental force. Though it doesn’t make much sense as supporting an individual right to have and use guns for personal self-defense, which has nothing to do with “tyranny” — unless he is suggesting that the Second Amendment was intended to permit individual political fanatics to start murdering their neighbors or assassinating elected officials if their party loses an election.

I don’t think Moros believes that, so it is hard to see a connection between this passage and an individual right that is disconnected from or unrelated to the collective or militia right.

Henry Flanders, 1860

Here, Moros doubled down on the insurrectionist view, which I think is distinct from an individual right to own guns solely for personal use or self-defense.

Moros says, “The idea that the amendment exists to defend against tyranny is often derided as the ‘insurrectionist’ theory of the 2A and considered unserious by modern academics. But so many of the 19th century texts embrace it.”

I agree with him that lots of writers in the Founding era, and especially in the decade leading up to the Civil War, embraced political violence and bloodshed that conscientious people would find reprehensible today. This type of bloodthirsty political fanaticism is what caused the unprecedented carnage and massive loss of life that occurred in the Civil War.

I have questions for modern proponents of this view. Who decides what counts as “tyranny” to justify gun owners going on a killing spree and shooting their neighbors who voted for the opposite political party? Is a policy of universal medical coverage or student loan forgiveness “tyranny” that justifies murdering one’s neighbors, relatives, or co-workers? What about background checks for gun purchases?

How can a democracy (or a republic) function alongside a system that permits people to build a personal arsenal and then go on a murderous rampage if their side loses any election or any vote in the legislature?

That being said, Moros is right that plenty of writers in American history thought violence was justified and/or necessary to force their political will on others, and many gun owners think that today. Even so, this “insurrection” view is distinct from personal self-defense. The former is about bearing arms for a greater cause, to save the country or the state or the community. The latter is completely self-interested, focused on bearing arms to protect one’s own property and family members.

Most writers who embraced the “insurrectionist” view did so under the premise of a collective right – that is, the citizen militia would come together to resist a tyrannical government. The early writers in the “insurrectionist” school of thought were not advocating for a Heller-style individual right to have guns for no other reason than personal self-defense.

Joseph Bartlett Burleigh, 1852

Moros then says, “same idea here,” and provides this excerpt:

I think he means this is more of the “insurrectionist” view, but this supports my contention that the insurrectionist view was originally a “collective” right, not an individual right to protect oneself with guns.

Burleigh is talking about disarming the entire populace and prohibiting military parades, not about restricting certain individuals from owning guns, limiting how many guns someone can have, or limiting the types of guns people can have. This is not about the modern idea of an “individual right” to own whatever guns one wants.

Charles Sumner, 1856

I won’t include the excerpt here, but it is another text about “The Kansas Question.” The federal government tried to stem to violent clashes in “bleeding Kansas” over slavery by limiting the interstate transport of firearms, and Sumner was complaining about that. I don’t think this is very illuminating about the original public meaning of the Second Amendment in the 1790’s. The federal government thought they could do what they were doing in 1856, even if some southerners decried it.

Anna Laurens Dawes, 1885

Kostas then quotes Dawes:

Once again, this writer places the Second Amendment right in the context of “the fundamental law that the militia should be organized and preserved.” This is the collective/militia right, not the individual right.

Furthermore, Moros admits that Dawes is “no fan of concealed carry,” but it’s more forceful than that. Dawes states that the Second Amendment allows statutes that prohibit carrying pistols (handguns): “This practice (carrying handguns) is dangerous in every way, bother on account of the rash action of angry men, and the added danger in occasions of tumult and riot.”

So she recognizes that it is fine for the legislature to restrict carrying handguns because of road rage incidents, drunken bar brawls, and so on. This does not support Moros’ view of an individual right to bear arms. This goes against what Moros advocates.

Laura Donnan, 1900

Moross then quotes this odd excerpt from Laura Donnan from 1900 (too late to be relevant, according to the Supreme Court in Bruen).

I understand that some of this sounds like it affirms an individual right distinct from the militia right (the section he highlighted). But notice what follows – prohibitions on concealed carrying are permissible (hard to reconcile with Moros’ view of an individual right to carry guns solely for personal self-defense). She continues, “It means they may have them for drilling purposes.” Indeed, those eligible for militia service would need to report every few weekends for mandatory drills. She does not say anything about it being permissible to have guns for shooting burglars, muggers, etc.

Charles Chadman, 1899

Moros then cites Chadman from 1899, once again too late to be relevant under Bruen):

So this says the Second Amendment does not protect concealed carrying of weapons, noting that these are “chiefly useful in individual encounters.” I take that to be a repudiation of the idea of an “individual right” because an individual right would only be for “individual encounters.” The fact that the right to bear arms extends beyond those currently “enrolled” in the militia means that it applies to all those eligible for militia service, whether or not they are on active duty.

This excerpt is consistent with the collective right view, and hard to reconcile with the modern individual right view.

Andrew White Young, Salter Storrs Clark · 1880

Again, “warlike weapons” refers to battlefield weapons for the collective right (militia service), and it says that the point is to be able to resist a standing army. The individual right is not about standing armies versus militias, but about using one’s firearm for oneself alone.

Part 3 will conclude this series with a historical analysis of the term “bear arms” and an update on the current Supreme Court’s stance on individual rights in the Second Amendment.

Dru Stevenson is Wayne Fischer Research Professor, Professor of Law at South Texas College of Law.

Image by Gordon Johnson from Pixabay.

"As seen from the discussion above, “warlike weapons” were not the same as the weapons an individual would normally carry for personal self-defense, or use to defend one’s home against an intruder. These were battlefield weapons."

Of all the disingenuous points in this weak attempt at a rebuttal, this one is far and away the most offensively stupid. There was absolutely zero difference between "battlefield weapons" and "the weapons an individual would normally carry for personal self-defense, or use to defend one's home against an intruder" until the last few decades of the 20th century.

During the Framing era, the Brown Bess musket and the Kentucky long rifle were both standard-issue military and common-use civilian weapons. This state of affairs persisted for nearly two centuries: through the Civil War (percussion muskets and revolvers), western expansion (lever-action repeating rifles and revolvers), World War One (bolt-action rifles, revolvers, and, increasingly, semi-auto pistols), World War Two (semi-auto rifles and pistols -- CMP sold millions of surplus Garands to civilians following the war), and Korea (same). It wasn't until the 1960s, when standard-issue military rifles started to become capable of fully-automatic and burst fire modes, that there was any meaningful difference between "military" and "civilian" weapons -- and even then, civilians bought (and continue to buy) millions of crippleware semi-auto versions of the military rifles (since, to the surprise of exactly nobody except pig-ignorant gun control advocates who barely know which end of a firearm is the shooty part, the same features that make a firearm good for killing enemy soldiers on a battlefield also make it good for killing the kinds of lawless goblins that a civilian might sometimes encounter).

The idea that Pomeroy, writing in 1888, would have made the slightest distinction between the "military" and "civilian" weapons of the day is completely preposterous, BECAUSE THEY WERE THE SAME WEAPONS (i.e., breech-loading rifles and single-action revolvers).

If everything you think you know about history comes from listening to hacks like Saul Cornell, you're woefully out of your depth.

My response, for those interested:

https://twitter.com/MorosKostas/status/1686810935271542784