Armed With Reason: The Podcast - Episode 28

The dour connections of domestic violence and firearms

October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month. As GVPedia Executive Director Caitlin Clarkson Pereira states in this latest podcast, whenever we have a question about domestic violence research or policies, Rachel Graber is the first person we reach out to.

Graber is the Vice President of Government Relations and Advocacy at Jewish Women International. During this discussion, she lays out the many misconceptions and realities of domestic violence, and how they are supercharged by the presence of guns.

Backed up with experience, alarming statistics, and numerous outlets for help, Graber’s chat with Caitlin and GVPedia Founder Devin Hughes is intense but hopeful.

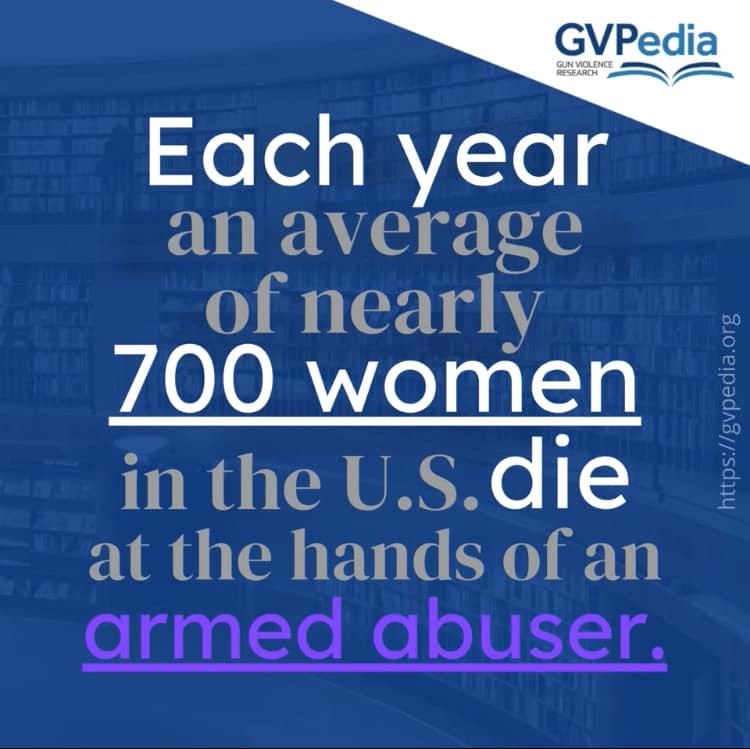

“We know that almost 14% of women in the U.S. and almost 6% of men have experienced some sort of threat by an intimate partner with a gun… And an average of almost two women are killed daily by domestic abusers with guns.”

You can listen to the podcast via our channel on Spotify as well as watch on YouTube, or read the transcription below.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPTION:

Caitlin: Hello, everyone. Thanks for joining us here on the Armed With Reason podcast brought to you by GVPedia. The month of October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month. And tragically, we know that guns have a lot to do with domestic violence.

Today, we are joined by Rachel Graber, who is the vice president of government relations and advocacy at Jewish Women International. Before her current role, she was the director of public affairs at the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Rachel has a wealth of experience countering the epidemic of domestic violence in the United States, and particularly the interest of guns and domestic violence. Here at GVPedia, whenever we have a question about research or policies concerning this issue, Rachel is the first person that we reach out to. So it's only appropriate that when it came to doing a podcast around domestic violence this month, we wanted to have you here, Rachel, to join us. So thank you so much for being here today.

Rachel: Thank you so much for inviting me. I have a friend who calls, I think she calls it like a mutual admiration society. I very much appreciate everything that GVPedia does to educate the world about the real research, accurate research, and data behind gun violence.

Caitlin: Thank you. I like that. That's a nice club to be a part of. I appreciate that. So again, here we are in Domestic Violence Awareness Month. Can you provide us with an overview of the role firearms play in domestic violence, and the impact that has on our country?

Rachel: Yeah, absolutely. And thank you so much, both of you — Devin and Caitlin — for inviting me on the podcast today to talk about firearms in the context of intimate partner violence. I am going to just use the term intimate partner violence interchangeably with domestic violence. Sometimes they can mean different things, but in this case I'm going to use them interchangeably. So as you know, the defining characteristic of domestic violence is the dynamic of power and coercive control exerted by the abusive partner against the victim. And access to firearms, it supercharges that dynamic, right? Domestic abusers use firearms to threaten, to physically harm, and far too often to kill their victims, their children, their pets, and also members of the community.

So we know that almost 14% of women in the U.S. and almost 6% of men have experienced some sort of threat by an intimate partner with a gun. Whether that be an explicit threat such as, you know, pointing a gun at the person and threatening to shoot them; or an implicit threat such as cleaning a gun after an argument, or leaving a receipt for a gun or ammunition in a prominent place where the victim will see it. So, you know, like I said, 14% of women have experienced threats. Of these, 43% of these women who were threatened with a firearm were actually physically harmed with it. In some cases that means being shot, but it could also be pistol whipped or sexually assaulted with a firearm. And, of course, we know far too often firearms are used to kill abusive male partners. Access to a firearm increases the risk of femicide fivefold — femicide being homicide of a female. And an average of almost two women are killed daily by domestic abusers with guns. And this doesn't even begin to count the people who are killed collaterally, which often includes children. So, you know, it's so common that, you know, killing the kids as well, that there's actually a term for it when the abuser kills his intimate partner and the entire family — it's called family annihilation.

Devin: Yeah. And one of the interesting, well, interesting / horrifying things, the Gun Violence Archive just recently has started going back and implementing the family annihilation criteria. And it's so often an element of gun violence that it's overlooked to a degree, because mass shootings, it's like, Oh it has to be public or something like this. And then you look in areas like Texas, Oklahoma, for example, where family annihilations are extraordinarily high, and it just doesn't reach national consciousness because it's like, Oh that was behind closed doors. And kind of going off of that, like domestic violence overall tends to be seen as something like, Oh it's like a personal, private thing behind closed doors just contained to that household. And it's a distinct problem from more public forms of gun violence. And yet I've seen a bunch of research showing the extent to the intersection between domestic violence and many other forms of violence, including mass shootings. So could you talk some about the intersection of domestic violence and other forms of violence?

Rachel: Yeah, absolutely. And that's it's such a great a great question. Before I talk about some of the ways domestic violence intersects with other forms of gun violence, I just want to address one frustration that I often have with how we talk about this particular topic. You know, sometimes when we talk about the intersection between domestic violence and other forms of gun violence, it feels like the lives and experiences of victims of gun-involved domestic violence, including domestic violence homicide, are given weight and importance not because of their intrinsic value, but because of who else the perpetrator might go on to kill. So, you know, I have seen factsheets about domestic violence and firearms, and the first thing is about mass shootings. And yes, those victims are very important. All victims are important. But talking about domestic violence victims, and I know that's not a belief that your listeners hold, that you hold. But I do want to name it because it's just so often the victims of domestic violence are viewed as being somehow complicit in the abuse, or blamed if the perpetrator goes on to kill other people. Right?

Devin: Yeah, it's like, why didn't they see it coming and do something about it?

Caitlin: Why didn't you just leave?

Rachel: Right. And and if you put, you know, mass shootings as the first thing on your domestic violence fact sheet, it's not about then, you know, you're losing that domestic violence angle. You know, so a person who's killed by an intimate partner is just as dead as a person who's killed by a stranger. And their life has just just as much worth. And they're never responsible for the violence perpetrated against them, or against anyone else. So I know that's not a thing that you all need to hear, but it is just something that always comes up for me when we we have this conversation. So I just kind of want to acknowledge that, put that out there, because if I'm feeling it, I'm sure other people are as well.

So that all being said, we do know, of course, that armed domestic abusers pose a threat to people beyond their immediate victims. They'll often target family members, as we talked about, including children, friends, coworkers, law enforcement, and complete strangers. So, you know, we know about 20% of people who are killed in domestic violence homicides are someone other than direct victim of the domestic violence. An abuser's use of a firearm in particular as a means of murder increases the risk of collateral homicides by 71%. And 1 in 4 of these collateral victims are children. So put another way, 1 in 3 children under the age of 13 who are killed by firearms are killed in domestic violence related incidents.

You might also have heard domestic violence calls are among the most dangerous situations to which law enforcement responds. A 2017 report found that a plurality of law enforcement deaths in the preceding six years had been the result of domestic violence calls.

And then, of course, mass shootings. As we know, most mass shootings have some sort of intersection with domestic or family violence. So between 2014 and 2019, almost 60% of mass shootings were related to domestic violence. And in 68% of mass shootings, the shooter either had a history of domestic violence or killed a family member. So at the same time, as we're saying, domestic violence victims should be valued in their own right. We also know that they are, I don't know how else to put it, but a canary in a coal mine for broader homicidal acts and behaviors.

Graphic created by and courtesy of GVPedia.

Devin: And to kind of go off of that real quick, your response really made me think of what about the inverse of that? Because where, like, domestic violence is seen like canary in coal mine, are there areas where the intersection of domestic violence and guns, are there other aspects of a canary in the coal mine, as it were, for that we can be on the lookout for.

Rachel: That's a really great question. And it has been kind of on my perennial to-do list to to do a little more digging into that realm, particularly as it pertains to community violence intervention. Right? Because we're investing so much in digging into that area right now. And, you know, as we are investing in saying, okay, here's some holistic supports that we can provide so that you don't pick up the gun, I would also like to kind of look into how we can include domestic violence in that, and saying and in addition to not picking up the gun, also don't beat up your girlfriend. And how can we support people to do that? I believe, but I wouldn't quote me on this — although I'm saying it in a public forum so somebody can fact check me — I think that Ujima, which is the National Center on Violence Against Women in the Black Community, is doing some work in that area. And so they might be a good follow up to answer that question.

Devin: And there's probably the potential for like hospital-based intervention programs. I know there's work out there looking at like, Hey, what are the warning signs for additional public violence? And so if some of that could be turned to look at domestic violence and those sort of risk factors, I think that could also probably be quite a useful area of study, to where it's like you're catching an earlier canary in the coal mine, and like using domestic violence as a canary in the coal mine, because it's like it needs to be stopped before then.

Rachel: Right, you have plenty to do.

Devin: Yes. Yeah. We just all need to get on there.

Rachel: Clone ourselves?

Caitlin: Yes. So, as you were speaking, Rachel, this thought just came to me, so I apologize if it comes out a little bit complicated, but, so we use the term date rape a lot, right? Versus rape. Rape, like you're walking down the sidewalk and some stranger jumps out from behind the bushes, right? Which we know is a ridiculously tiny amount of the rapes that actually occur. And then we use date rape as a way to place blame typically on the victim. Like this is somebody that you knew, you got in the car with him, you had drinks with him — and I'm using him just because that's the majority, but we know that's not the only situation that sexual assault occurs. But, you know, what were you wearing? How much do you have to drink? Like all those questions start to come to light in those situations.

So do we think when we're using the term domestic violence, that sort of natural draw towards victim blaming, you know — you knew he was violent, and why didn't you leave? Why didn't you think the kids? Like all those sorts of questions also sort of organically come to the surface? Is that a similar vernacular situation that we're in here, or am I making that up?

Rachel: You know, I'm not sure that I know the answer to that question. It's a very interesting question. I do think that when we talk about domestic violence, in many cases there is an element of victim blaming. And that's something that the domestic violence field has spent a lot of time pushing back on. And a lot of that, honestly, from my perspective — and this is just me riffing, I suppose you would say — is based on an assumption that men's experience of violence and women's experience of violence is the same.

So going off a little bit off on a tangent, when we talk about things like medical research. And for so long they viewed womanhood as being a confounding factor. And so men were the control group, right? And women had like little additional complications. And it feels in a lot of ways kind of that same just really basic misogyny — preferencing men's experiences as actual reality, rather than recognizing that men's experiences and women's experiences of violence are very different. Because men are much more likely to be harmed by a stranger or kind of a more distant acquaintance. They're far more likely to be harmed by multiple assailants. Whereas women it's very, very rare that a woman is harmed by a stranger. It does happen, of course, but usually it's an intimate partner. We know that most homicides of women are committed by individuals. Right? But in homicide, in violence, in sexual assault, it's an intimate partner, a husband, a family member, a father, a brother, an uncle, a grandpa or, you know, a so-called friend or a family member. And people don't want to think about that. They don't want to think, Oh someone I know could hurt me. It's, I think, emotionally easier for people to have that stranger danger frame.

Devin: It reminds me of like a few months ago — sorry to interject — but the whole would women rather encounter a bear or a random guy in the woods. And it's like, yeah, there's definitely a lot of risk-based calculation there, but also kind of like it's not the stranger that's typically the threat in many of these domestic violence situations. It's somebody you know. And I do think there's kind of a cultural not wanting to go there almost, if that makes sense.

Rachel: You know, it's the sanctity of the family. And there's not a whole lot of sanctity in sexual violence or intimate partner violence.

Caitlin: Well then a lot of us said we'd pick the bear, and then the man would get very angry at us. And we're like, well, now you wonder why we pick the bear? Because this has nothing to do with you specifically, and somehow you're still getting mad. But that's a tangent.

Rachel: Going to be honest. I think I would rather just, like, not get lost.

Caitlin: Right. When when life allows us the opportunity not to be put in those sorts of situations... Maybe there's a way that we could we could say that that's similar to having a certain level of privilege, right?

Rachel: A very high level of privilege. And I mean, that's a thing. We know that one in, actually is higher now, I think the most recent statistic that I saw was 2 in 5 women will experience intimate partner violence that has some sort of like IPV impact — whether that be an injury that requires medical attention, or law enforcement involvement, or legal services, or something like that. That's 40% of women. And intimate partner violence impacts people from all walks of life. You know, people who are wealthy are not immune. People who live in certain parts of the country are not immune. People who, you know, I mean, there are communities who experience intimate partner at disproportionate rates, mostly based on, you know, long-term systemic racism and long-term systemic inequality and oppression of communities.

But gender-based violence can happen to anyone. And it's really easy to say it could never happen to me. Everybody says that before it happens to them, right? I mean, that's not true. People who have experienced it in the past who've seen it growing up might not have that. But for a lot of people, you know, nobody goes into a relationship assuming that it's going to be abusive. Because at the beginning, relationships that become abusive, they seem wonderful. You start out with a relationship that's, often in many cases, it feels too good to be true. Right? You have all that love bombing and the kind of really two, I guess, expedited timeline for emotional ties. And it's not something that people can necessarily predict or manage the risk going in; and making assumptions that they can again, is this blaming victims.

Caitlin: Right. And unfortunately, classic abusers are really good in the beginning of relationships of convincing the people that they're with that they are quite the opposite of that.

Rachel: They are master manipulators.

Caitlin: Yes, for sure. So I'm going to change directions to restraining orders here. So both domestic violence restraining orders that remove guns from an abuser and extreme risk protection orders are both seen as tools that we have to help reduce instances of domestic violence. Can you talk a little bit about these tools, and how they're not exclusively interchangeable? And of course, these are also with caveats that in different states these things mean different things.

Rachel: Yeah, absolutely. And as you well know, I get a little agitated when people tout extreme risk protective orders, also known as ERPOs, as a solution to domestic violence. So bear with me. You know, the irony, of course, is that extreme risk orders are actually based on domestic violence protective orders, which I will often refer to as DVPOs. Still many syllables, actually. But they are designed for different types of circumstances.

So both DVPOs and ERPOs are court orders that restrain the respondent from engaging in certain actions. But DVPOs address a range of actions related to domestic violence that include but also go beyond firearm possession, whereas ERPOs exclusively address firearm possession. This is, of course, because ERPOs are intended to intervene in cases when someone is experiencing a temporary crisis that might make them a threat to themselves or others. So this might include something like suicidal ideation, drug addiction, the loss of a loss of a loved one or of a job, a mental health crisis, or some sort of other other situation that just temporarily makes it dangerous for them to have a gun. But the ERPO, it doesn't provide any remedies to address whatever the underlying crisis is. Right? It doesn't provide mental health supports, or grief counseling, or job training, or anything like that. The only thing it does is it takes the gun out of that equation. And we know how important that is, to take the gun out of the equation. We know that for every ten ERPOs issued, we know that one person is alive today because of those ten ERPOs. Firearms, they are much more lethal. And if they're immediately available, you don't have that time to think, to make a decision the way that you would if you were having to take extra steps to either attempt a suicide or a homicide.

So in contrast, domestic violence protective orders (DVPOs), they address the holistic needs of victims of domestic violence. So they take the guns away and they address all of those other things that a victim needs. They can order the respondent to stay away from the victim and their family and not to contact them. They can temporarily address child custody and custody of pets, assign like the use of a commonly owed residence or a car. They can require the respondent to get counseling, or drug treatment, or participate in a better intervention program. They can prohibit the respondent from removing the victim and their kids from an employer-sponsored health insurance plan or shared phone plan. Just so many different types of relief that protective orders can provide to victims to address the lived experience of people. And, of course, we know federal law prohibits certain respondents to DVPOs from having guns. State law also does in many places.

And then, of course, the gun prohibitions can be written directly into the text of DVPOs. Often you have all three right in the same protective order. And of course, then federal law explicitly requires full faith and credit to be accorded to DVPOs across state lines. So while in almost every situation involving domestic violence, a DVPO is the more appropriate avenue.

There might be some cases in which a domestic violence victim would prefer an ERPO, and that's why it's so important to have it in the tool box. But it's really important that the victim be the person who's making the decision, and they make that decision without any pressure. Because the victims, they're the only person who can truly understand their situation and what will make them safer versus what will increase the danger that they face. So, of course, domestic violence is escalatory in nature. And engagement with a court can increase the risk of violence against the victim. So that being said, sometimes a victim might want a third party to petition for an ERPO to get their guns taken away without their name being attached to the case. And then the removal of the guns might create a situation in which you can take further action to protect yourself, including possibly taking it, seeking a DVPO. But on the other hand, if you know a well-meaning friend or colleague who has legal standing to petition for an ERPO does that without the survivor asking for it, that can cause the abuser to escalate and take it out on the victim, and again can increase the danger.

So, you know, in any situation, any action must be taken with the knowledge and the consent of the victims. You know, one thing that we've heard that's very frustrating is that sometimes law enforcement and courts will enforce ERPOs, but not DVPOs. And I just want to say, you know, that doesn't mean that victims should have to go through two separate court proceedings to get the relief to which they're entitled under a DVPO. So that's an indication that this system is broken.

And you know, I'm just going to say it straight out — the jurisdiction needs to reject the misogyny that values some people more than others, that values the safety of the people who are subject to VRPOs and the people around them over the safety of victims and survivors of domestic violence. You know, so court watch programs and police accountability boards can be really helpful in holding such jurisdictions to account. You know, if you're looking for support to improve your jurisdiction's response, the Battered Women's Justice Project; the National Center on Domestic Violence and Firearms has a lot of really great resources. So if you're having trouble in your jurisdiction, I recommend reaching out to them. And also at the National Center on Protective Orders and Full Faith and Credit.

Devin: I'll return to the broken system in a moment, but before going there, a quick question on myths. Because one of the things at GVPedia, our primary focus is countering disinformation on gun violence. And oftentimes we see the gun lobby and its allies telling women, like, Got a domestic violence situation? Get a gun and that'll protect you. And so what is the truth about women arming themselves, and what can women turn to instead of firearms to help?

Graphic created by and courtesy of GVPedia.

Rachel: Right. So almost a year ago now, the House Judiciary Committee held a particularly asinine hearing entitled Second Amendment Rights Empower Women's Rights. Did you all watch that?

Devin: I heard about it. I could not bring myself to watch it directly.

Rachel: It was a doozy. It was just as cringe as you probably imagine from the name, I know y'all do a much better job than I can at debunking myths about guns making people safer in general, so I'm going to put that aside and really talk specifically about the myth of firearms as a great equalizer for women. And that myth is based on a fundamental misunderstanding about who perpetrates violence against against women. And I think we talked about this before, the assumption that men's violence and women's violence experiences are the same. You know that it is really based on the misogynistic assumption that men are the norm. And also, it's not a reflection of reality.

So, you know, as we also talked about earlier, most women are murdered by men they know. And so proponents of of arming women to protect themselves from domestic violence and rape, what they're actually saying is you should harm or kill your husband, your boyfriend, the father of your kids, your uncles, grandmas, your friends, your classmates, your coworkers.

And we also know that so many victims and survivors who actually do defend themselves then end up criminalized themselves. And, of course, urging women to arm themselves to prevent domestic or sexual violence, that comes perilously close to victim blaming, right? It puts the onus to prevent violence on the victim, not on the perpetrator.

But, you know, kind of beyond the philosophical objections, we also know it just doesn't work. Research shows that firearm possession is not a protective factor against domestic violence. Women who experience DV possess firearms at the same rate as those who don't. And there have been a bunch of studies kind of looking at this from different angles, but they all come to the same conclusion. And just to put it bluntly, more guns means more dead women. A study in California of women who purchased firearms found that a purchase of a handgun increased the risk of homicide by 50%. And firearm homicides specifically, the risk doubled. And those increases were due entirely to an increase in intimate partner homicide risk.

Similarly, if you look at the study, there was a study that used the density of federal firearms licenses as a proxy for legal gun ownership. They found a higher rate of homicides in areas with more gun ownership, but that was driven entirely by an increase in intimate partner homicide. So more guns — it doesn't matter who owns the guns — more dead people. More dead women in particular.

And drilling even further down, more dead victims of domestic violence. And we know that a victim's firearm can easily be used against her. And as Caitlin said, we know that intimate partner violence happens to people of all genders by all genders. But in most cases, it is a man perpetrating against a woman. And so a male abuser's access to firearms, regardless of who owns that firearm, increases the risk of a femicide at least fivefold, if not more. There are different studies, some place it as high as 11; and some, there was one that that specifically said that the biggest red flag, the single largest predictor of intimate partner homicide was the presence of a gun.

So if somebody does feel that the path forward for them is to arm themselves, we definitely encourage them to make sure you know how to use your gun. Make sure that you are, if God forbid, you ever need to use it or choose to use it, that you're going to hit what you're shooting at. You're not going to hit your kid or the person standing near you. The gun isn't going to be taken away from you. You'll be ready for recoil, all of those things. And that, you know, you're going to hit what you aim at. And that requires extensive training, and ongoing training; and also that you store your gun safely. Again, not only to make sure that your intimate partner doesn't get it, but also to make sure that your child doesn't accidentally access it, that you know, in a moment of despair, use it against yourself, that it's not stolen and diverted into the black market. But in general, we would recommend not getting a gun.

There is a substantial victim service infrastructure throughout the United States. So we would encourage victims and survivors who are looking for help to reach out to either the National Domestic Violence Hotline at (800) 799-7233; or to a local domestic violence program to get help. And if you call the hotline, the hotline will refer you to a local program, if that's what you're looking for. So, you know, a domestic violence advocate, they can help you with safety planning. They can help you with relocation. They can help you engage with the legal system. Like whatever the survivor, a victim, or survivor needs to be safe for them and their family.

Devin: And so to go into kind of like the system as well — as listeners of this podcast know, I'm from Oklahoma and there was a situation a few years ago where I was trying to help a friend out of a domestic violence situation. And there was a long history of abuse, both physical and mental. Like the police had been called several times before. They had actually handed her a card of a domestic violence nonprofit, and the state had the wrong number on it. And so, like during this point, I tried to get her out of this situation because I also knew the guy had guns, and just like took her to the domestic violence nonprofit. They provide a list of resources. I called all of them. None of them replied. And during it, I also called like the suicide prevention hotline because there were moments of breaking for her. And like, I could literally hear the guy Googling, like with my answers because I was like, What do I do here? Like, do I break this person's trust and have medical intervention? Or where's the dividing line here? And in the end, she ended up going back to the abuser.

And it was just trying to [use] resources, and then all these resources just weren't appearing. I was like, what can people do who don't have access. Like, Oklahoma is an anti-ERPO. Like if there's not those resources, and I wouldn't have been able to access those resources because no law enforcement or court or so forth. Like, what can people do to help in those situations?

Rachel: Yeah. And I'm so sorry about your friend. Honestly, it's not uncommon for victims and survivors to return to abusive partners sometimes because it's actually safer for them. Because at least in there, they know what he's doing. And sometimes it's because they don't have anywhere else to go. But victims and survivors are kind of always managing that risk. And they're managing risk to themselves, but they're also managing risk to their friends, to their families, to their children, to their pets, to their communities. And I think it's very, very painful to have someone you know and you love be going through that and feeling helpless. Right? Or feeling like you tried to help and there was just nothing you could do. And honestly, the most important thing you can do is to be there for them. One very common tactic that abusers use is to isolate their victims from friends and family.

Devin: Strip away all the friends.

Rachel: Yes, exactly. And so, you know, it might be like, Oh I haven't heard from you for two years. Where did you come from? Or, you know, Well you chose him over me. And, you know, he was probably — I'm saying again, he or she in a very generic sense — the abuser is probably feeding the victim all sorts of lies about their friends, their families, their neighbors, the people who they relied on to create that isolation. And so reaching out to you — not you particularly, you in kind of a generic sense — is an act of trust and an act of courage. And so to be there, to be present, and not to judge, not to tell them what to do, and don't say bad things about the abusive partner. Because again, a survivor might feel like they have to defend their partner.

And one of the really complicated things about domestic violence is that you often have at the same time co-occurring fear, terror, hatred, and love. Right? Because there are those times when the relationship is wonderful. And a lot of survivors, they don't want to leave the intimate partner, they just want the abuse to stop. That's what we hear over and over and over again from survivors: "I don't want to leave, I just want him to stop abusing me." So just being there, so that when they're ready to take those next steps to leave the abusive partner, that you're a safe person to whom they can go for help. And if it takes them a couple of times to leave, that's common. People very commonly say it takes seven times for a victim to to finally leave. I have searched and searched and searched for the providence of that statistic, and I have not been able to find it.

Devin: Yeah, I heard 13 at the nonprofit. Haven't seen the source.

Rachel: Yes, I have not been able to find that source, and I have looked. So whether it's 7 or 13 or 5 or 20, it is true that it often takes many times, because the abuser comes and says, "No, I've learned my lesson. I've changed. I love you. It will be different, I promise." And then, I'm a bad person. And then you feel like you have to take care of them. I mean, there's all sorts of emotional manipulation. So it's very common.

And sometimes, you know, there aren't resources. And we've seen a very dramatic cut in funding for victim services this last year. And, you know, I think programs do the best they can with what they have, but we always need more. But I think the one thing I would just reinforce is that they know their situation best, the victim or survivor know their situation best. And in many cases, they can tell you what it is they need. And then, you know, basically what you did, Devin, is just making sure that you knew what resources were available in your area and were able to provide that information. It sounds like, you know, the resources in your area were overburdened and not able to provide the support that this particular survivor needed, which does happen. But at least being able to kind of make that initial connection.

Caitlin: Yeah. Here in Connecticut, I years ago had to file for a protective order, which is exclusive of an intimate partner. That would be a restraining order here. And it wasn't until I had to go through the entire system that I realized again how privilege plays a big role in your access to resources. I had the Internet to find all the phone numbers, I had the time off from work, I was a native speaker of the language, and I had a support system. And I just remember trying to find my way around this world.

And for every answer I got or didn't get, or voicemail I left, or email, or desperate question that I was throwing at random people on the phone hoping they would track me in the right place — I kept thinking, what does somebody do who doesn't have all of the abilities that I have simply because, you know, my lot in life has given me those. And I can't imagine having to navigate that system quietly because you don't want somebody to hear you, or on your lunch break at work maybe that you get, or not speaking the language, or whatever it is. We talk about these services and they are so critical. But the only way they make a difference is if people can get access to them first.

Rachel: Yeah. And I mean, it's a constant struggle, and we're always trying to get more resources. Also, don't forget to call your members of Congress and tell them to fund victim services.

Caitlin: And vote! Although I don't necessarily think we need to tell our listeners to vote, but just in case. Rachel, can you let our listeners know where they can learn more about you or your organization, if they'd like to follow you on social media, websites or what have you, just so they can learn more after this episode?

Rachel: Yeah, absolutely. You can check our website out at jwi.org. We do work in both gender-based violence and gun violence. And I don't do social media personally.

Caitlin: Probably better that way.

Rachel: I found it to be very bad for my mental health actually. Our Instagram is @JewishWomenIntl. Our Twitter — I will never call it X — I can't tell you what it is because it's behind a paywall because I'm not signed into X.

Caitlin: Also probably better that way.

Rachel: It's probably the same thatt our Facebook is, Jewish Women International. If you want to get ahold of me, you can find me on LinkedIn. I will admit that I don't always answer instant messages because I get a lot and I try to minimize my social media, but I feel obligated as a professional to view LinkedIn. Or you can just drop me an email: rgraber@jwi.org. I will just tell you in advance I am not a victim advocate, so I probably am not going to be able to be super helpful if someone is looking for services. I can of course provide referrals, but I'm happy to answer any questions or be helpful as I can.

Caitlin: So again, here we are in October. And it's important that we bring awareness this month. But there are 11 other months of the year. And just as you were saying earlier, that domestic violence doesn't discriminate for a myriad of other things, it certainly doesn't discriminate based on the month that you're in. So hopefully we can continue these conversations on the macro and micro levels due to fantastic folks such as yourself being such critical proponents in this field for us. And you know, there's amazing people that are boots on the ground in this, doing this work every single day. So thank you for being here, for answering all of our questions, and for supporting a cause that certainly needs as much support as it can get.

Rachel: Thank you both so much for having me. And can I officially call myself a friend of the podcast now?

Caitlin: Absolutely! Yes. Yeah. If you're on social media, we could tag you in that and call you that. But I think it's better to stay off social media. We'll just put in an email for you and make you a certificate, or something like that.

Rachel: My parents will be so proud.

Caitlin: They will be. Alright Rachel, well, thanks so much again, and we'll talk to you soon.

Rachel: Thank you. Take care.

Photo by Marvelous Raphael on Unsplash.