Armed With Reason: The Podcast - What's the 18th Century Got to Do With It?

Noah Shusterman, historian and author, discusses the knotted roots of our current Second Amendment debate

In GVPedia’s never-ending quest to debunk, today’s new podcast goes back to the 18th Century to really dig down into the roots of the Second Amendment misinformation that currently dominates the pro-gun movement.

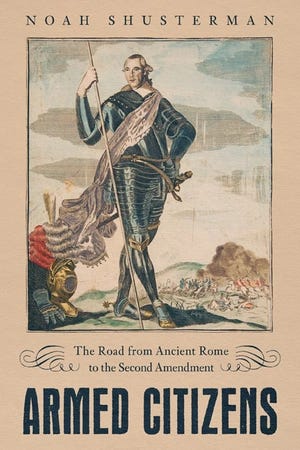

Our guest is Noah Shusterman, Associate Professor in the Department of History at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, whose work focuses on the French and American revolutions. His latest book, Armed Citizens, the Road from Ancient Rome to the Second Amendment, explains the origins of 18th Century militias and the ongoing debate about our “right to bear arms.”

You can listen to the podcast via our channel on Spotify as well as on YouTube, or read the transcription below.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPTION:

Caitlin: Hello, everyone. Thanks for joining us on the Armed with Reason podcast brought to you by GVPedia. This is our second podcast of the decade. And even though it's been a couple of months, it certainly has been a very interesting amount of time that has lapsed. It feels like a thousand years have gone by. But to avoid discussing the present — and for some self -preservation — we've decided to delve into the past with today's guest, Dr. Noah Shusterman, who is a historian at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is the author of Armed Citizens, the Road from Ancient Rome to the Second Amendment, which the title suggests is a couple millennium long journey through the history of citizen militias.

Avid readers of our Substack may recall that back in July of '23, Dr. Schusterman wrote how to be a Second Amendment absolutist in which he talked about the original purpose of the Second Amendment and how strikingly different it is from how it is promoted today. So Noah, thank you so much for joining us from literally across the world in China. just a couple hours time difference. We really appreciate you taking some time to talk with us about your book and your research here today.

Noah: Oh, thanks, Caitlin. Thanks, Devin. Thanks for having me. Yeah. Here in Hong Kong, it's a different world, and yes, it's tomorrow here already.

Devin: You're already a day ahead of us.

Caitlin: That gives us hope that at least the world doesn't end tomorrow because you're currently in it. So to get us started here, would you want to tell our listeners what motivated you to research 18th century militias, and how their presence impacts the Second Amendment?

Noah: Well, like a lot of people, Sandy Hook was a huge shock to me. I was at the time, I was trained as a historian of Europe, and specifically I'd done my first two works on 18th century France and the French Revolution. And I was wrapping up my second book, and Sandy Hook happened. And partly, it's just, you know, as an academic, you're looking for what do I do next? But I knew in a sort of very general level that this was, you know, the Second Amendment is an 18th century document. It's, you know, it comes out of the ideas of the 18th century. I had some general familiarity with some of those ideas with, you know, in the French Revolution, you get this idea of coming from Rousseau, in the French case, that every soldier should be a citizen and every citizen should be a soldier. So I knew there was some link there. And I just, I thought I would start trying, start digging around, start seeing what I saw. And hopefully in some, you know, minor tangential way as a historian be part of the solution. And that's it. That's my origin story.

Devin: So a question I can't resist asking is given that the title of your book, do you think about Rome every day? Like apparently 90 % of all men in the U.S. do. And then like one of the things that strikes me is why were the founding fathers so invested in the citizen militia-based concept, given as George Washington stated multiple times that the actual state militias tended to perform rather poorly relative to the continental army and more formally trained military formations. And so what caused that sort of we need to go in the militia direction approach.

Noah: Two very different questions. I'll do the Roman one first because when this was coming out, I remember it was specifically how often do you think about the Roman Empire? And I think about the Roman Republic. When I started looking at all this background history, I tried to be true to my training. I tried to just go in and see what's there, see what I can find, because there's always gonna be something new that you can find. And you find a lot of references to Rome, a lot of references to Julius Caesar, Julius Caesar is the man who killed the Republic. And so yeah, I do think about Rome a lot, but I think about it in a very specific context, and I have no desire at all to go back to it.

Now the bigger question is this militias question, and I wouldn't have phrased it in that way. You know, I kind of work in a few different subfields when I'm doing this research. And one of them is this group of writers, mostly who wrote in Great Britain in the late 17th century, but also includes Rousseau, who I mentioned before, who are so into the militias and have this vision of society with an active militia system where not only are the militias this great fighting force, but the militia service makes all men into virtuous and virile citizens. And nobody who grew up in the colonies — in the British colonies in North America — thought that the militias were any of that. You know, they'd all had their militia service. They'd all been to the militia trainings. Some of them taking part in the militia actions during the war, they knew what the militias were. They knew that they were a weak fighting force. They knew that they wouldn't have defeated the British if they hadn't had the Continental Army, and really if they hadn't had the French Royal Army.

It wasn't that. It wasn't that they thought the militias were so great. It's that they thought that the alternative to the militias was a standing army. And they had this sense that a society with a standing army.... So people differed on a society with a large standing army or a society with any standing army — this was the bone of contention — couldn't really be free. So how do you avoid having any sort of professional army? Well you avoid it by having a citizen's militia instead. So it wasn't a love of militias in the case of the Americans, it was this fear of standing armies that led them to make a lot of the decisions they made.

Devin: Today, we have the most powerful standing army in the world, still rather substantially. So like it's kind of interesting how the main driver behind the Second Amendment and the embrace of militias has been fully realized in the form of the U.S. Military. And as you mentioned in the piece [you wrote] for us, now a couple years ago, that there's almost a central hypocrisy of sorts with those who claim to be fully supportive of the Second Amendment. I don't think any of them say in the next breath, and I want to abolish the United States Armed Forces. Like, it's not a thing. And so how do we juggle this kind of anachronistic fear of standing militaries and having the largest standing military in the world; and what sort of impact does it have other than kind of mass confusion?

Noah: So there is a mass confusion, mass misunderstanding. There's a bunch of reasons why this fear of standing armies doesn't resonate today. And one of them is that when you're talking in the 18th century, when people were talking about a fear of standing armies, there wasn't some fear that the standing army would go wild and, you know, and invade Canada again, you know, that we would send off ships to go invade Spain, or anything like that. But they're also...

Devin: Oh, we might invade Canada again, but we promise not to go into current events too much.

Noah: I don't mind going into current events in some general senses. So the deal is that this distinction we have so thoroughly in our minds is that we have an army that deals with external enemies, and we have a police that deals with domestic matters. And that is a 19th century distinction. I mean it existed in the 18th century, but it was very faint. The British fear of standing armies wasn't that the army would go run wild in Spain, or even in Scotland or Ireland. The fear was that this army would run wild in England itself, and that the army would impose itself on domestic politics. So when we're looking at the fear of a standing army and why we should fear it — because I do think that there's some wisdom there — we need to look at what's happening within the United States.

We need to look at what's happening, well first off, what's happening with this attempt to politicize the army as much as possible, but also this fear that, well, how do I rephrase this? The fear of a standing army was about an army that ran roughshod over the citizens it was meant to protect. And this is something that we would associate now with an out of control police force, not an out of control army. But it's a fear worth having, this fear of a criminal and unaccountable internal militarized force is what the founders were talking about when they talked about a fear of a standing army. It had nothing to do with our troops that are stationed in Okinawa, our troops that are stationed in Europe. I've lost track of where they are, where our troops are stationed. But it's not the men and women we send overseas. It's not the Navy in the aircraft carriers. It's the people who are stationed within the country itself. And the lack of a militia that could defeat the British Army wasn't going to change that at all.

Devin: Yeah, and it's also kind of interesting/weird where you have many of the strongest proponents of, or people who claim to be the strongest proponents of the Second Amendment are also like waving the thin blue line flag for police officers, very strong pro -law enforcement, except in certain cases, and also very strong pro -military, which are kind of the two things that militias were sort of supposed to take care of. And so just curious about that sort of balance, or again, just kind of lack of historical awareness and understanding.

Noah: Remember there was this brief moment where Oliver North was, you know, the head of the NRA, sort of the titular head. And literally at the time Queen Elizabeth would have been a less anti-Second Amendment choice. This idea of a military that acted on behalf of the executive and yet was doing so to break the the laws that the legislature had said — this is exactly what the second amendment was meant to prevent, this lawless military system. And yet we have this, you know, pro-military group that calls itself a Second Amendment group. And the other thing, if the right wing, this conservative movement, this pro -gun movement — to speak about it in a very general sense — if they were just gonna say, "We want a Second Amendment for the 21st century, we believe in the values of widespread gun ownership, and we think that there should be no infringement on the right to bear arms," there's a certain logical consistency there. It's not mine. You know, I don't understand wanting to tolerate this level of gun violence in the country and gun intimidation, but it makes sense. This is the society we want.

But somewhere along the line, the right wing attached itself to this idea of originalism and that we wanna go back to the founder's intentions. And so you have these most ridiculous pretzel twists of logic and contradictions and hypocrisies, where if they would just say, “Actually, you know, we're not originalists, this is the society we want,” we could have a more honest debate about what kind of society we want.

We don't have this, you know, like attempt to turn the second amendment into something it wasn't. Because the second half of the amendment, it is pretty clear. Like you read it and you understand each word, you understand, you know, as a gun violence prevention advocate, you understand that there's something to go up against it, in an amendment that has this very clear second half. Whereas this first half, you know, for most people its meaning isn't clear anymore. And if we were just to say, you know, like, okay, this doesn't make any sense, and let's just have the society we want. You know, you can have a more honest debate about this. But this whole, you know, "We are the true originalists" thing, it winds up in some very dishonest places.

Caitlin: Do you think that what our definition of an army or a militia a couple hundred years ago or a police force even a hundred years ago — I mean initially we're talking about when your arms were a musket and a bayonet at the end, right? And so it's extremely different than what we have witnessed be invented and manufactured over the past 200 or so years. So in some ways, especially when someone says they're an originalist, as much as I want to throw like the three fifths compromise back at them, there is the part of my brain that's like, okay, so let's turn in all your guns and give you a musket. Because that's what the intent was. And it was a completely different sort of warfare that existed simply because they didn't have access to automatic and semi -automatic weapons.

Noah: If you want to accomplish something by force in the 18th century, you want men. You want men, you want horses, ideally you want cannons, and yeah, you want muskets and bayonets. It's a huge advantage to have muskets and bayonets over not having muskets and bayonets.

But this idea that we've got one person, two, three people, but we've got a semi-automatic or a fully automatic rifle and we can just shoot up the place, that wasn't part of the calculation. So the whole system they set up, it wasn't gun-centric in the way that our thoughts on the Second Amendment on all these issues are gun-centric [today].

And so yeah, you're not going to get people to just embrace the musket, you know, unless there's some sort of historical reenactor.

Devin: I was just going to kind of add on to that, back then there really wasn't the personal self-defense type element. I mean they did consider personal self-defense to be important, but it wasn't necessarily like with muskets forming a line, and then firing volleys, and then reloading for 10, 15, 20 seconds, and then firing another volley — like that doesn't really work for personal self-defense. And then like with flintlock muskets or flintlock pistols it's a pain-and-a-half, as my history major brother tells me. And so it's just like the weapons in that era weren't particularly... or like the gun wasn't the great equalizer or self-defense mechanism that many people seem to assume it was. It was more like collective defense form — all the able-bodied white guys at that time into a line and repel a raid or whoever's coming to threaten things.

Noah: Yeah, yeah. The key at the time was to have a large group of organized men working together according to an established hierarchy, which is, you know, not to deny the military potential of women, but they were not, in the 18th century, they were not thinking it that way at all.

Caitlin: We mostly died in childbirth anyway, so we didn't have time to run around with guns in the field. But that's a story for another time.

Noah: But yeah, no, I mean, now a woman with an AR-15 can do just as much damage as a man with an AR-15. But they weren't thinking along those lines in the time, and they weren't going to have women out there working the cannon, which, you know, women could have done at the time, but that was not there. You know, what are the men fighting for if not for their women? And that was much more of the mindset at the time.

Caitlin: Chivalry.

Devin: And gold. Lots of gold.

Caitlin: So one of the reviews of your book said, quote, now that we see why we are doing what we're doing with guns, maybe we can do something different, end quote. So what are we doing with guns? And how does it deviate from the actual history of the Second Amendment?

Noah: I don't know what we're doing with guns. It doesn't make any sense to me.

You know, one of the things that's pretty obvious once you've left the U.S. is that there's no desire on any other nation to be more like the U.S. when it comes to gun violence. And even the people who are very pro-U.S. outside of the U.S. or, you know, pro-U.S. in different ways — usually, it doesn't mean being pro-Trump, it means being, you know, pro-Taylor Swift or pro-NBA. They'll be pro-U.S. despite the gun violence, not because of it.

And this is where I do say I'm a historian, I'm an academic, you know, and I'm trying to help. But when I'm honest about it, I'm not helping much. Um, you know, you two are the ones who have to, you know, go through the political issues, you know — how much political capital do we have, and how do we want to prioritize that political capital? And those are questions where I stay out.

You know, I get frustrated about some things. It's clear to me that having assault rifles in the U.S. does far more harm than good. But is an assault rifle ban, even in good political times, is that how we can save the most lives, how we can most improve U.S. society? That I don't know. Taking guns in a way that certainly nobody in the 18th century would have wanted. That said, what you do see in 18th century U.S. — well you know, in the British colonies and then the 18th century U.S. — is an enormous tolerance for white violence, not just white violence against people of color, but what we would call white-on-white violence. You know, Shay's Rebellion, the Whiskey Rebellion, these were pretty ugly.

Devin: And even like the Tea Party, where it's like, yeah, that was basically domestic terrorism. It ended up like, "Yay, Constitutional Republic," but still, like, it was not a nice act.

Noah: Yeah, and we tolerate it. The penalties for the people who took part in Shae's Rebellion and in the Whiskey Rebellion were extremely mild in a way that obviously, Gabriel's Rebellion, which was this warded revolt of enslaved people, those were not mild. Those repercussions, those penalties — if you want to call them that, they were more just random white violence against black people — those were not tolerated. But there is a kind of tolerance for white violence that seems to be built into U.S. society, in part because there's a hesitancy to use the, what would you call it, the coercive power of the state against white Americans. Which if that could spread to all Americans, it's good to limit the use of the coercive violence of the state. But it plays out in, "Oh, somebody shot up another school, but what're you going to do?

Caitlin: Right. Yeah. It's never time to talk about the politics related to it, right? It's always too soon.

Devin: I guess January 6th has an originalist history where it's just like, Storm to the Capitol? Nah, you're good.

Noah: Yeah.

Devin: And it does kind of remind me, there's this one story of gun violence from I think it was 18th, 19th century, where of course white guys. But it was in Tennessee, and there's this argument between these two neighbors. And one of the neighbors came over to the other guy when he was on his porch, started arguing. And so the guy on the porch got a shotgun and blew the other guy away. And the lawyers for the case thought that they had a slam dunk, like the guy's not denying he did this. This is clearly murder. And the jury returned the unanimous verdict of not guilty. And when asked, they were like, well, he wouldn't have been a man if he hadn't defended his honor in such a way. And so it's just that sort of violence is baked in.

Caitlin: Yeah, and gender stereotypes and toxic masculinity. I know I'm probably not allowed to say that anymore.

Noah: I'm thinking about Rand Paul right now.

Caitlin: Oh gosh, oh no. When presenting your research or speaking about your book, what sorts of reactions do you receive from people, and are any particularly surprising to you?

Noah: Particularly surprising, no. So I've been — partly because I'm on the other side of the world, partly because I'm an academic, I'm at home by myself with a pile of books or a pile of archives or a computer — I'm not as active in promoting as I should be. Mostly, when I have had chances to talk to people who aren't historians, It's just, you know, people have no idea. You know, people don't understand this fear of a standing army. People don't understand why, you know, where these ideas came from. People don't understand that there's a historical background to all of this. So, it is a whole new world that's opening up to them. Not that they necessarily want to pursue it, but they, you know, they have no idea. This idea that we should be scared of our own army is just not on anybody's radar.

And, you know, there is this weird thing, you know, standing army is a term that only comes up in these discussions, because it was the term that people used in the 18th century. And for whatever reason, we haven't said fear of a professional army, or just fear of an army. But people are surprised, people who thought that they knew, to some extent, the earlier era. And you know, I would like it if there was some way to have broader discussions with people who aren't so close to my own background, my own priorities. But there isn't much of a space out there for a well-thought discussion of this. I'm trying to remember the name of the woman, I think it's Joyce Malcolm.

Devin: Yeah, her research became so popular at the Supreme Court.

Noah: She has this great article from early in her career about the English Civil War. And it's about how, you know, it's kind of a very basic question. England had basically had no army until the 1640s. They just had this militia, and they knew that the militia wasn't very good. And then the fight over the militia is one of the main bones of contention. Parliament tries to seize control of the militia; the king says the militia belongs to the king. And this is one of the things that pushes the two sides to go into actual civil war with each other. For non-historic listeners, 1642 is when the English civil war began with parliament on one side and the king on the other.

Devin: And the king ended up a head shorter at the end.

Noah: Yes, and both sides had to go and raise armies. And so that brings up this very basic question. Like, how do you raise an army? Like there's been no army. How do you raise an army? And that was the question that Joyce Malcolm tried to answer in this article. And it's just a fascinating article because I think it's a very basic question, and it's hard to answer. And she does a good job of it. And that's been one article like any other historian's article or historical scholar's article that, you know, gets maybe a couple dozen readers and fades off into the sunset.

Meanwhile, she's written some very weak stuff, trying to sort of pidgeon hole everything 17th and 18th century into this 20th and 21st century individual rights model — and that's the work by her that gets recognized and gets cited. And it's not good work. It's not, you know, for any real scholar, it's not convincing. But people want to be able to say, oh, this historian or this historical scholar provided proof for what I've been wanting to say anyway, and so that's the one that gets the attention. Which, by the way, The Second Amendment, a Biography...

Devin: By Michael Waldman?

Noah: Yeah, yeah. I like some of Michael Waldman's work, other work, but that book is the same. Like, I'm going to take this early history and piece it into the format I want. Now, I want the format that Paul Waldman also wants. I don't want the final solution. Not final solution — sorry. I want the societal answers that Paul Waldman wants and not that Joyce Malcolm wants. But his book, as a historian, has the same issues. We're going to take this 18th century material and make it fit the 20th and 21st century answers we want. As a historian, that's not the training I have. That's not the approach I want to take. But I got off on a long tangent. I think that they're gonna be people whose approach to life, approach to society, isn't going to be mine, but who would be very interested in this 17th, 18th century vision of a society where men had certain virtues, possibly applicable to women as well, of a commitment to society that includes military training, that includes looking after others, that includes being ready in case of emergency, and that they carry this notion of citizenship with them wherever they go. But it's part of a unit. It's a little bit different than Jennifer Carlson's work on citizen protectors, but it's a kind of message that people would want to hear. It's just that if it doesn't fit into this, you know, Scalia, Thomas definition of the Second Amendment, they close their ears.

Devin: Yeah. And to kind of go into that, one of the more annoying parts to me is kind of the rise of law office history, which tends to involve doing a search on Google Scholar, highlighting some words, and being like, "A-ha, it was an individual right all along!" type approach, or just seizing on particularly weak work and ignoring the entire context around it. And then that gets amplified by the gun lobby's firehose of falsehood, which can take scholars who are barely scholars or had good work elsewhere, but not on this. And then just dial it up to 12 out of 10.

And to kind of go into a technical question, one of the talking points I frequently here is that "well-regulated" doesn't mean what it means today, which I believe is accurate. It meant well disciplined at the time, which still implies militia. And that "keep and bear arms" clearly means an individual, not collective. I've even had a pro-gun lawyer talk about, like, how can a collective keep arms? And it's like, have you ever heard of an armory — like the things that the British were trying to raid that set off the entire war? That was the kind of final spark on a long list of sparks on the path to the Revolutionary War. So one of the fields that I've been kind of interested in seeing the results from is corpus linguistics, and going into how documents used to cite "bear arms," or "keeping bear arms," and "well-regulated" and such. And my impression of that field of work is that it's largely refuted, like the purely individualistic, like there wasn't a militia component really to it. But I'm curious about your take on this sort of dive into the weeds.

Noah: I've only kind of been somewhat aware of the corpus linguistic stuff. To me, the idea that you do historical research by looking at each word and its meaning doesn't get you very far. It's not an approach that historians usually take. I mean, it's very useful, obviously, if you can look at and see like this word that meant X in the 21st century meant B, or Roman numeral II in the 18th century, and it's nice to have that knowledge. But I tend to take a broader view of this. And a couple of things happen.

One is that, it's at a very basic level. When I started doing the historical research into this, I assumed I was doing the history of the whole Second Amendment. And the second half of the Amendment just didn't have much history to it. It says what it says, you know, and like I said, there's an interpretation that says forget the history, it says what it says. And, you know, and we could have a debate about that. But you know, I'm an historian, I need to write things that talk about what I found, and I didn't find much on the second half; and I found a ton on the first half. So that's where I followed the research, that's where I followed the material. And I found that there was a lot to say there.

Now there is a basic issue historically about trying to understand what does it mean for the people to have a right to bear arms. And to me it comes down to who were the people who had this right? And I don't think that corpus linguistics part is where I would look for the answer. I'm talking about Rousseau for a third time. Rousseau is very clear about, you know, a human male is at once a man and a citizen. He's a man as a private person — first as a son, then as a husband and a father. But as a citizen, he takes an active participation in the world. He participates in politics, he participates in debates, and above all, he participates in the militia. He was Swiss, the Swiss had this militia system that was the envy of Republicans — lowercase r — across the 18th century world. And so as a citizen, you bear arms for your nation. Now in Switzerland, as in all of the colonies, every colony and then every state had regulations that said, like you said, every able -bodied male — and there'd be some age range like 16 to 50 or something like that — shall be part of the militia, except for the government agents, and the reverence, and whatnot, and teachers usually. And so when they are bearing rights, when they are part of the militia, when they have their weapons, whether they're kept at home or whether they're kept in the armory, and with some musket, you know, it's not that big a deal if you're taking it home or if you're leaving it at the shop. Who are you? Are you the man or are you the citizen? You're the citizen. And so unless you can separate the citizen from the man, you can't say whether the individual has that right to bear arms as the citizen or as the man.

The fact was that, you know, everybody had this right to bear arms as a member of the militia. And so these two were inseparable. Does that make it an individual right? It doesn't not make it an individual right, but it doesn't definitively make it an individual right, because these two things are so muddled up with each other.

Devin: It's kind of a muddy area that just from today does not make sense, but back then, definitely applied. And I'm glad you brought up Switzerland, because I feel like that's a country where that's kind of the originalist meaning if there is any, of the Second Amendment there — everybody has military training, but yes, you can take your service rifle home, but there's been some regulations around that. And if you use it at all, like if you strip off the covering for ammunition, you're in major trouble. Like that's not meant for carrying around in public, it's not a self -defense weapon — it's for service to your country.

Noah: Switzerland, Israel, this is another can of worms, South Korea, Singapore, they have a sort of universal male, or in Israel's case, male and female military system. It's much closer to what the 18th century had in mind.

One of the things I said about Heller... you know, this question about is there an individual right to bear arms? Like, it's the kind of question that deserves a five-four answer…. It's not the kind of question that a historian would ask, because it's not a question that the founders asked. It's not a question that the people of that generation asked. You know, it's our question. And you can try to find an answer, but you know, forget about being anything to do with original issues.

Devin: I mean, I personally wouldn't have that big a problem with Heller if the justices had just been, "All right, it's kind of outdated. Here's what it means now." I don't think it's the best decision, but fair enough, like that's what you think it is. But to say, Oh, this is what it's always meant based on our understanding of the past" is just to me profoundly dishonest. And to kind of ask one question to wrap up because one of our major focuses here at GVPedia is countering disinformation, the way we mostly focus on the public health data rather than the legal or historical information out there. But what's some of the biggest pieces of disinformation you encounter in today's debate over the amendment, and in particular in the Heller and Bruin decisions?

Noah: Well, I'm not sure there's any new ones, in the terms of things that we haven't already talked about.

Heller and Bruen are themselves disinformation. Heller, in claiming that this was the reason that there was a Second Amendment; Bruen, in claiming that the second amendment was about self-defense. Heller is readable, and you can read it and disagree with it, even though he calls me grotesque, which I resent. Bruen is not readable, it's not anything you can take seriously, it's just kind of Clarence Thomas saying, I'm a Supreme Court justice, and I'm deciding this, and you can't do anything. They are themselves disinformation to the extent that there's anything historical going on there.

There exists this whole collection of historical discussions of the Second Amendment that try to... you now what? I'm going to change gears here. Here's the one that bugs me. There is an entire book called That Every Man Be Armed. I want to say it's by Stephen Halbrooke. And the point of the book is that this whole idea of the Second Amendment...

Devin: That Every Man Be Armed: the Evolution of the Constitutional Right by Stephen Halbrooke. Yeah, and it's on second edition, which kind of shuttered me that they have multiple editions of that, but it's from 1994. So proceed. I just wanted to put that in there.

Noah: Thank you. [That title] is from a debate, this is a Patrick Henry quote, from a debate where he's talking about the militia in a debate that he lost. So the idea that this line is somehow proof of a desire from the founders for an individual right to bear arms is just so far gone from what was going on in the 18th century.

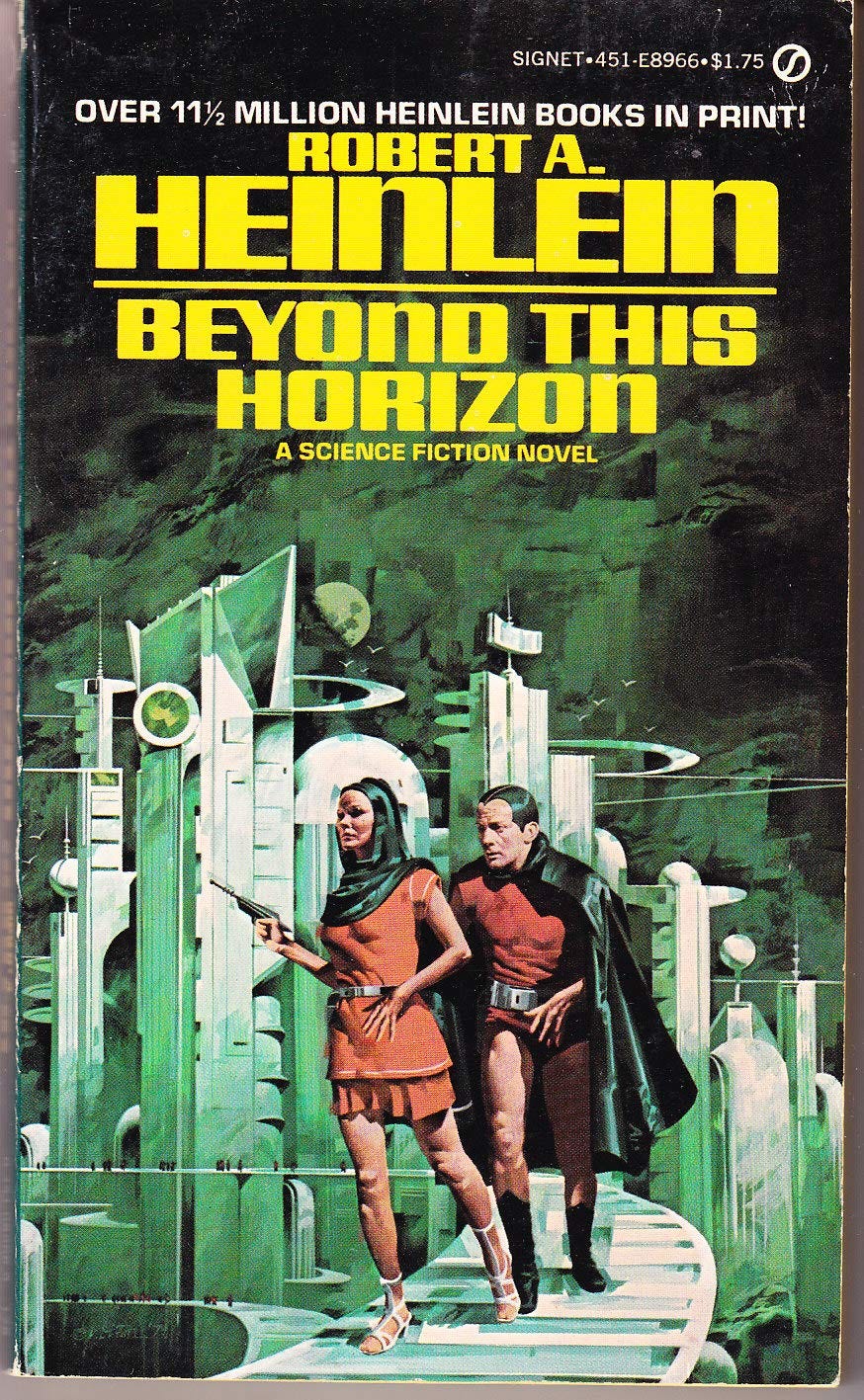

Devin: That kind of reminds me, I'm sorry to go on one final tangent at the end here, but the whole catchphrase — an armed society is a polite society — and pro-gun people and organizations like, Oh, what a fantastic quote that really speaks the truth. And it's from a 1950s science fiction book (Beyond This Horizon by Robert A. Heinlein) that centers on a society of genetic supermen that are deeply chauvinistic and like dueling each other to the death to prove their manhood. And even in the book, it's very clear that "an armed society is a polite society" is not true. Like then the author goes to great lengths to be like, Yeah, this is nuts. Even in this, it's insane. But now it's pulled out, like it's a fiction in the science fiction novel, and then it's pulled by pro-gun advocates as like, Ooh, this is a foundational truth. And it's like, you clearly haven't read the source material here. But yeah, it's kind of like the Patrick Henry quotes and misquotes and everything.

Noah: Did not know that's where that came from.

Caitlin: So I would just like to thank you again for coming here. We've definitely taken enough of your time tonight, and Devin would love to talk with you about this forever. So maybe we can do like a second edition, and Devin can take questions, and it'll be a whole event. But if you wanna let us know where our listeners can find you and your book, we're happy to have you throw a pitch out there before we sign off today.

Noah: So I have a needs-to-be-updated website — noahschusterman.net. And the book was published by University of Virginia Press. I'd love it if people ordered either directly from them or for those lucky enough to still have a local bookstore to order it through them. And a handy tip for anybody who wants to read academic works. Academics love it when people reach out to them and say, I'd like to read some of your work. We'll send you PDFs. We don't need the royalties. I shouldn't speak for everybody, but generally speaking, academics like to hear from readers, especially non-academic readers. We're happy to share our work. We're happy to discuss things in most matters. Anyway, the thing I'd like to say is both thanks for having me on and thanks for all the work that the two of you do. It's a kind of daily grind that I couldn't do. So I'm glad that people like you can.

Caitlin: Thank you, we appreciate that. And we will be sure to share all that information and your website with our listeners when we post this. And thank you for writing for our Substack in the past, and if the mood ever strikes again, feel free to submit something, you know where to find us. All right, thanks so much.

Noah: Thanks, bye Caitlin, bye Devin.

Image by WikiImages from Pixabay.