Armed with Reason: The Podcast - Facing Trauma with Advocacy

A conversation with gun reform advocate and survivor, Khary Penebaker

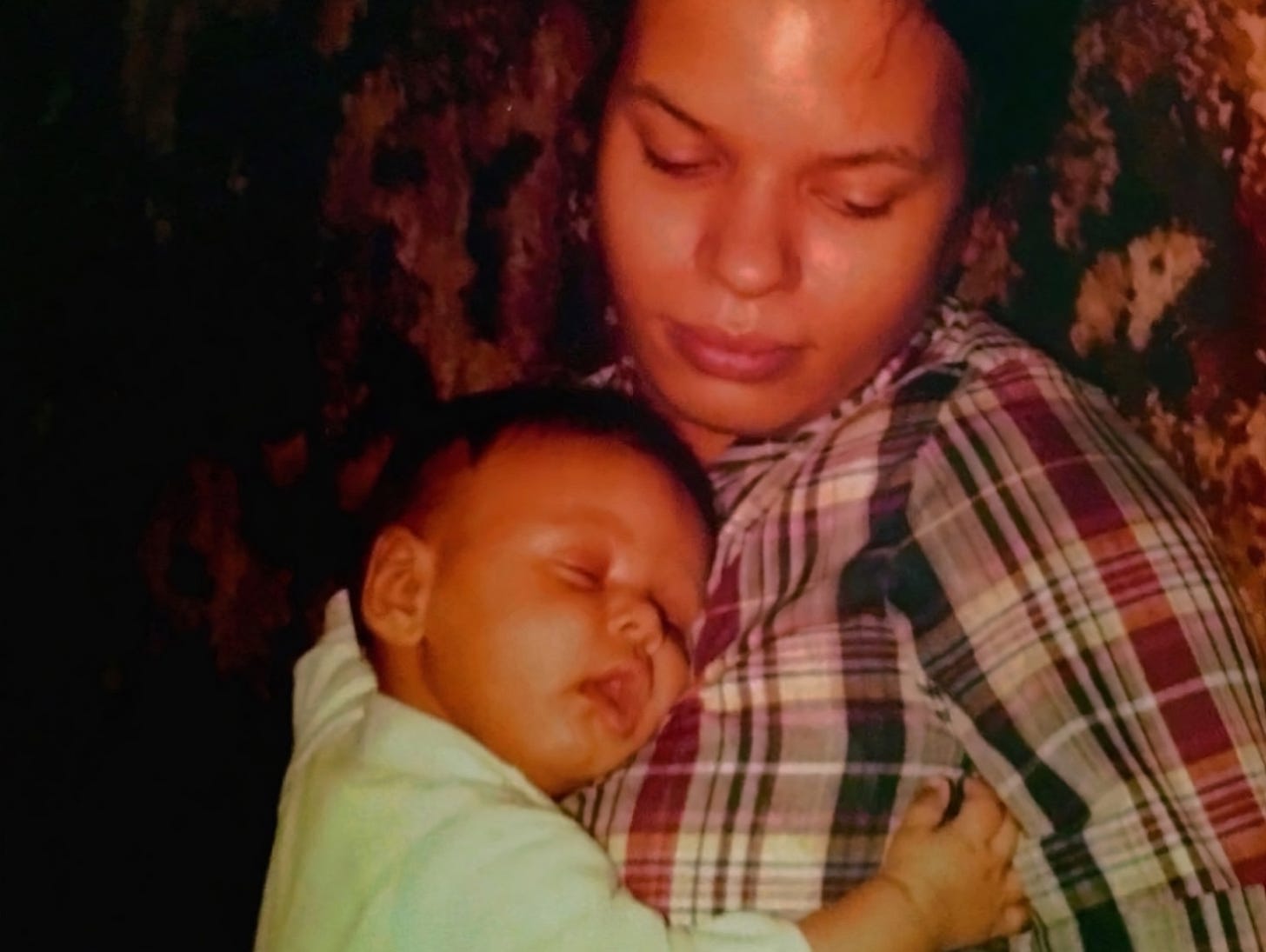

Khary Penebaker and his mother Joyce

Episode 37 of the Armed with Reason podcast is a conversation with Khary Penebaker, a nationally recognized advocate for gun reform and dedicated leader within the Democratic Party and Everytown for Gun Safety as Wisconsin's Survivor Fellow.

Penebaker’s activism developed out of a profound personal loss — his mother Joyce tragically took her own life when he was just 20-months old. Penebaker explains how he came to terms with the loss, survived suicide himself, translated his feelings into political action, the struggles of honestly refuting the barrage of disinformation from the gun lobby, and how even loss in political life can be chalked up as a win if we continue to bring gun violence prevention to the top of social and political discourse.

“When you think about gun violence prevention, it's not some numbers, not some statistic that bleeds. I don't sit a spreadsheet of numbers in a chair at Christmas thinking it's my mom, right? There's a human being missing. Those numbers don't bleed like our loved ones do. So if we talk about these things from a human perspective, there's no no way we can't win.”

You can listen to the podcast via our channel on Spotify as well as on YouTube, or read the transcription below.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPTION:

Caitlin: Hi everyone. Thanks for joining us here on the Armed with Reason podcast brought to you by GVPedia. I think Devin and I fancy ourselves rather accomplished individuals, but sometimes we are humbled to have guests here on our podcast that make us think, yikes, I have a lot of work to do. And today's guest is definitely one of those people.

Khary Penebaker is a nationally recognized advocate for gun reform and dedicated leader within the Democratic Party. His journey marked by personal tragedy and unwavering commitment to public service has made him a prominent figure in Wisconsin and across the United States. He experienced a profound personal loss at a young age. His mother, Joyce, tragically took her own life when he was just 20-months old. This event has deeply influenced his lifelong mission to prevent gun violence and to support mental health initiatives. Khary's advocacy works gained national attention through his involvement with Everytown for Gun Safety as Wisconsin's Survivor Fellow. He has shared his personal story at numerous rallies and events, including a high-profile appearance in a Mike Bloomberg campaign ad in 2020, which underscored the urgent need for gun reform.

In 2016, he ran for Congress in Wisconsin's Fifth District, bringing attention to critical issues such as universal background checks, economic development, and public safety. His leadership extends beyond gun reform, and he is actively involved in efforts to combat climate change, improve public education, and enhance economic opportunities for underserved communities. Again, I am terribly impressed by your body of work and all the advocacy that you have done. So thank you so much for taking some time to join me and Devin here on the podcast today.

Khary: Yeah, thanks for having me.

Caitlin: So to start off, do you mind just telling us a little bit about your story and how you became so involved as a gun violence prevention advocate?

Khary: Yeah, so years ago shortly after or shortly before the Sandy Hook man shooting, a friend of mine was and he still is a tactical arms instructor and he was having a class, I think it was like December 26, 2012. So just it was scheduled already for just a few days after what would be the Sandy Hook mass shooting. So I didn't, obviously I could not foresee the future. But at the time I was not really, I was in politics a bit, but I wasn't at the level I would get to. So I agreed to take the class because he needed just more people to fill the space. It was for concealed carry permit here in Wisconsin. There is no actual time limit on the class itself. You can actually take a class for 10 seconds and get your permit. Actually you have to go through more training here in Wisconsin to get a license to be a hairdresser than you do to have a concealed carry permit, which is ridiculous to me. But Tony is a fantastic human being, and his class was four hours. Also in Wisconsin, you are not required to do any live shooting, and Tony's class did not involve any live shooting. It only involved the use of a prop gun so you could get used to holding it. And the class really was not about how you could be John J. Rambo, it was more about how you can disengage from a potential threat, not how you become the savior of a mass shooting. But he also taught the law. And then going through this, you know, I at the time was a relative novice in the in the GVP space. And I just didn't think of things in the same terms that I do now.

So I completed the class, and when I got home I told my my ex-wife — my wife at the time — that I had done this, and I want to buy a gun for the house. And she was like, you of all people should know better of why you should not have a gun in the house. And I'm like, what are you talking? You know, obviously I knew, but I didn't put it in the context of me in the proximity of a gun. I was just thinking about the home safety aspect. And she was like, you know your mom completed suicide. Why would you want to, you know, introduce something like that into this environment? I'm like, well, I didn't really consider it from that perspective, but let me do some research. So that's when I found at the time was called One Million Moms for Gun Control maybe that Moms Demand Action used to be; and then it was also I think it was called like Mayors Against Illegal Guns at the time. And Milwaukee's mayor at the time was also one of the founding members.

So I had written an email, and they were doing this bus tour and stopping at random cities and reading up the names of fellow gun violence survivors and victims, and they read my name. And it was one of the people involved in the mayor's side had reached out to me, and we just became friends. I started talking to him more about what was going on. And then, you know, Moms Demand formed shortly thereafter. They merged with Mayors Against Illegal Guns and formed Everytown, and then Moms Demand Action. And then I just got involved, um, partially because I didn't know who else to talk to. It was really like someone had ripped the bandaid off of a decades-old wound of not having dealt with the trauma of losing my mom. And not just losing my mom, 'cause that's one thing — whether you lose your parent or loved one from any tragedy, illness, or whatever, that by itself comes with its own set of trauma. But when you introduce the gun violence side, it's a whole 'nother thing. And I just hadn't processed any of it. And then in the process of being involved in all of this advocacy, I was forced to address my own trauma. And that's what took me the longest to deal with. And that kind of, I mean, that's a longer story. But that really is where the trajectory took me along with the advocacy, when I learned how to advocate.

I mean, you just can't do that. It's not something that you would innately know. You have to learn how to talk, learn how talk to legislators, know what to say, know what not to say. All those things. You're being on national TV and in magazines and newspapers and all the extra stuff that comes from that. But it opened my eyes to what the issue required. It can't just be Shannon Watts. She needed advocates who had experienced gun violence to help share their stories. When you got someone who is a champion like she is, you need to be able to bolster her energy with the faces of gun violence. And people like me helped her do that. And we were able to take a movement and an issue to a place it really had never been. And there were some fantastic things that we accomplished, and some terrible things that many of us had to experience, but that really is the nuts and bolts of my story.

Caitlin: Do you think before Sandy Hook happened, and before that gentleman reached out to you and that's when you started to get involved, did you realize the impact that the story about you and your mother would have?

Khary: I did not think about it in terms of the impact it would have on other people in the community. I thought obviously I was facing it's never ending impact on my life. Whether you're looking at things like Mother's Day, or my wedding, or the births of my children. And those are some common things that I would talk about when I would tell my story. Like those basic things that you experience with your parents that I didn't get to experience with my mom. You know, when you couple that with both suicide and gun violence, it's like a perfect storm of tragedy that really doesn't have a dummy's guide on how to process.

But at the time, I did not, I just, I didn't consider the impact on the broader community. And it's not like I thought I was alone, but it really felt isolating because in my circle, I was the only one. And I think that is common for most people where whatever tragedy you're facing, you might know from a 10,000-foot view I cannot be the only one. But in that moment of isolation, you do feel like you're on an island. I'm the only person on the planet ever made that's got to face this level of tragedy, and it's crushing. I mean there were moments where before all of the advocacy self-started where it was almost immobilizing where I wasn't able to function because of those, you know, traumatic experience.

And most notably like on special days like Christmas, which is often the worst time of the year for me because my mom's not there. Or Mother's Day, which is the second worst day of the year for me. Or her birthday, which is a third worst day the year from me. So when those days would come, like there's no roadmap on what to do. Now, I will say having gone through therapy and all that, I have a better set of tools on how to manage those dark moments. But back then, and of anything, it was just the sheer will to want to get through it without knowing how to do so.

Devin: I'd like to return to something that you mentioned like early on, which was like you took the concealed carry course and were actively thinking of purchasing a firearm and thinking about the home safety aspect at the time. I'm curious, had you heard things like, Oh yeah, the gun will make me safer. Just kind of an underlying assumption that, okay yeah, this is a good idea for me to be responsible and protect myself and my family?

Khary: So that narrative is one of the older arguments that the opposition will levy on us about how you need a gun in the house to be safer. But statistics will tell you that the opposite is actually true, where you're more likely to harm yourself or someone you love than actually ward off an assailant. And I'm glad my ex-wife was aware enough to say, like, Hey, why would you want to introduce this into our environment where I had already been struggling with mental health to begin with?

At that point, I had attempted suicide three times myself, and I'm so glad I was not able to complete them. But when you have something that adds that level of finality to the equation, you have a higher chance of completion. There are very few people who were able to survive a self-inflicted gunshot one, especially one to the head. There's only a few stories you can find that are like that. And I'm glad that I'm not one of them. I'm I'm happy I was able to not do that, but I was under the assumption at the time that having a gun in the house would automatically make me safer, when in reality it would likely make me less safe from myself.

Devin: Do you have any sense of where that idea that like, Oh, this would make me safer, came from, or is just kind of like, in a way, fish swimming in the water sort of thing. And that's just the underlying assumption. It requires, like, what is water here, all of a sudden to even have an awareness of it.

Khary: No, it wasn't something that I thought was just like a given. It was an argument that I just simply had heard repeatedly. I mean, really, before Moms and Everytown every — I mean, you still had Brady, a couple others — but the issue itself was not as prominent as it has grown to be. And I'm not saying it's all Shannon, right? I'm not saying that. But a lot of it is due to the effort that she started. But prior to 2012 and 13, the kind of movement we have now didn't exist. So I didn't hear those arguments that support common sense gun reform. I really only heard that you need a gun in the house to be safe. In retrospect, I see how flawed that logic is because if you if your argument is you want to keep your house safe, why are we only talking about just the gun itself? We aren't talking about like no one's reading Home Alarm System Weekly, you know what I mean? So like it's easier for me to see it now having been through this experience for the last 15-plus years But I just didn't hear anything different back then.

Devin: Yeah, I do kind of wonder even with the changes since 2012 and 2013, how many people just don't really encounter the arguments there. And one of the other kind of talking points from the gun lobby — and it permeates much of society outside as well — is that like suicides just shouldn't count as gun violence, and it's like, oh, it's two separate things. If somebody's going to commit suicide, nothing can really be done about it. And so what's your response and reaction when people talk about gun suicides in this way and basically say that they aren't gun violence?

Khary: Yeah, so I get that often. That is usually the most common retort I get, is that this is not gun violence. My first response is the bullet that exploded in my mother's head did not do so peacefully. It exploded my mom's head. I'm not saying that in jest or to be trivial. It's literally what happened. It is a form of gun violence. The WHO includes self-inflicted violence as a part of its definition of violence. So I usually go to that end. And what's interesting is that I'll get that response from my detractors and from those who might support me simply because of the way that they think about it.

I did an event with Cory Booker here in Milwaukee. When he was running for President, I think 2019, give or take. And, you know, this room was full of like three, four hundred people in this coffee shop. And at the end, this guy who was clearly there to support what we had been talking about, said that very thing — that he didn't think this was gun violence, that it was a mental health issue. And it was like being punched in the gut. It hurt, it hurt more to hear it from someone who supports gun violence prevention than it did from a detractor because I don't believe detractors actually care about the issue. But this guy did, and it really did hurt. And once I was able to compose myself, I literally thought, like, I mean every issue of gun violence has extenuating circumstances, whether it's child access or homicide on the street, an unintentional shooting somewhere else, a mass shooting — it's never just one thing. It's always something else that leads to it. Mental health can be one of them, but it's not like well It's a mental health issue that gets put in a corner by itself. No. All of it is a part of gun violence, and I think we need to be honest about what gun violence is and its approach to it. I mean, think about it this way. If you had a family member who was a drug addict or was an alcoholic, would you leave open bottles of beer and whiskey around them? Would you leave open bottles or Percocet around them.? The answer clearly would be no. So why wouldn't we take the same kind of approach of prevention when it comes to someone who might be suicidal? Instead of allowing them to have easy access to a means of finality, let's prevent it. I'm not talking about being reactive. Let's be proactive so that you have fewer and fewer stories like my mom.

So that's really how I approach the issue of people saying it's just mental health or it doesn't count. You don't get to tell me what way this should be counted or not. The other thing I often hear is that like, if I think you even said it, like if she wouldn't have shot herself, she would have completed suicide another way. So you want me to imagine another way my mom could have killed herself. Think about that. I don't want to imagine my mom killing herself in any fashion, let alone a different one than the one she used. Like how much, how crueler do you want to be in your effort to defend a gun, to try to get a mother's child to imagine another way that his or her mom could have died? That is just cruel to me. And it just speaks to the kind of mental capacity or the deficit of mental capacity that people have who are advocates for guns when they don't think about the humanity of it, like the faces of gun violence. They're so in love with and so obsessed with the gun itself that they ignore the impact it has on actual people.

Devin: And one of the kind of things around that is, I mean, to me, it's always been rather straightforward and bizarre why somebody wouldn't include firearm suicides in gun violence, because the reason we're focused on the gun, which is a tool, is it's a very lethal tool. And that lethality carries through whether it's homicide, suicide, unintentional. It's because it's super lethal. Things that would be in public like a fist fight become a mass casualty tragedy; a suicide attempt that would be less likely to succeed in the home — and there's recourse to prevent somebody from committing suicide again — becomes final due to the lethality. And also there might be other issues like this out there, but gun violence is the only one that springs to mind where you systematically have people like, Oh, this shouldn't count. It's like, Oh, that was just gang violence — and for those listening to the audio I'm doing air quotes — that shouldn't count. Oh, it was gun suicides, that shouldn't count. Oh, I was just within the home, that shouldn't count. It was a mental health issue, that shouldn't count. And like, it's just like any little thing, Oh, that shouldn't count. And it's like, nobody's arguing that like it's the gun alone, but it increases the lethality of the situations that it finds itself in it massively escalates them. And so I definitely hear that frustration and share that frustration on that — where, like, when seeking to protect the firearm itself, like it's ignoring the humanity and just forming excuses in such a way that we don't really do with any other issue that springs to mind.

Khary: Yeah, and it's really unfortunate because you have so many people who bring a very disingenuous argument to the table, and they do so passionately. Well, again, like you said a minute ago about they just simply ignore the humanity of it. And they really fetishize the gun so much to the point where the human part doesn't matter. And every time I talk about my story, I do emphasize that I don't blame the gun. This wasn't an unintentional discharge, my mom didn't drop the gun and it went off, that didn't happen. She intentionally, at least in that moment, pulled the trigger. Granted, she was not in her right mind. Depression was clearly lying to her. But I don't blame the gun, I do blame her access to it.

And at the end of the day, that is the essence of what we are advocating for. It's the access. It's not the gun so much itself, it is the access to it by those who shouldn't have it. And I think that oftentimes gets ignored in favor of like the excuses you made a minute ago, they're trying to delineate these different segments. This can count, but that can't count. All these different things to try to minimize the overall impact on our country. So that they don't have to do anything about it. They have no real interest in solving the problem. I mean, the NRA has done a fantastic job of marketing. That's all they do. It is just pure 100% marketing. Because you'll notice that they aren't making claims right now about how we need to fight back against tyrannical government. That only exists when Democrats or the black guy is in charge. But when it's Trump, hey, no big deal. So they don't have an interest in solving problems with gun violence at all, they just want to sell more guns. But the more that they try to sell guns in the way that they're doing, the more stories like mine you'll have.

Caitlin: I don't think we need to dance around the issue. They're only interested in stating what works in their favor, right? So self-defense is why you need to have a gun. And that's how they sell guns, and that's they sell their conventions and their magazines and their sweatshirts and their stickers on their cars — which parentheses, by the way is like, Hey, break into my car because there's probably a gun in here. So that's why they're trying to, you know, if it's at home, if it is about the family, if it's self-inflicted, like those things don't count which just really makes no sense, but they've convinced themselves this is the reality; and they say it with such strong conviction that to other individuals who just aren't as informed for no other reason than they just don't live in a space where they have to think about it or talk about it a lot, it you know makes sense to them. We could probably talk about the damage the gun lobby has done for hours and hours

But Khary, can you tell us how your passion for gun violence prevention has fueled your political involvement? I mentioned earlier that you ran for Congress in 2016, and you also have been very active in the D-triple-C [Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee].

Khary: So in being involved with Moms Demand, I had been doing these advocacy days, as we all have done. And essentially, advocacy from a civilian perspective is you are basically begging a politician to do something. There's only a certain amount of time from my perspective that you can do that to the point where you realize, as all of us would say, you change the policy or you change the people that make it. And I got to a point personally where I got sick of begging people who have no real interest in making the substance of changes I believed in and that we were advocating for. So I was like, well, let me just take that next step and try to change the policymaker. And so even before I got to that, I was involved in our local party. I became the vice chair of our the 5th CD executive committee. That's the committee that's charged with trying to find the candidate for Congress to run in the 5th Congressional District. Here in Wisconsin, our 5th CD is deeply red. It is about as red as you can get. I think at the time it was like an R35 or something crazy like that.

I'm not built to think I'm going to lose. I mean, side note is I wish I would have gotten the kind of training that would have prepared me for losing, because I think that ultimately hurt my long-term political career because I'm not built for it. I'm just built to believe I can win. And I ran on a policy of gun violence prevention, women's reproductive rights, and student loan debt reform in a district that was deeply red where my opponent had 100% name recognition and had not lost in my entire lifetime. That was up against a political behemoth, and I didn't care. I just believed that I believe so much in the issues that I stand for, and the positions that I stand for that how can I lose? That if you just take the message to the masses that you you're going to win, that's not the case in every situation, But you have to have someone who's willing to start those conversations for the future people to step in and feel more comfortable talking about those issues in races.

We didn't have someone like me before in this seat, or at least in that race, talking about gun violence prevention, we just simply didn't do it because it's a deeply red district, 720,000 people who most of which would subscribe to an argument from the NRA. I'm like, you know what? I'm not willing to give them the home run on this. I'm going to make them fight for it. We had done well relative to like, I think we did better than like the last three or four candidates that had run in that seat, something like that, combined. And then you had more people wanting to run for the seat after that. We haven't won it yet, but we've made dents in it. We've helped other candidates down ballot do better. But it really did open my eyes to how the sausage is made from a political perspective. You really do see that some of the things that you think happen, don't.

When I got elected to the DNC in January, I think it was March or somewhere in there, it was the earlier part of 2017. The very first thing I did, because I went to our, it was like, I think June, it was our summer meeting that year for the DNC, and they had this video of the house members who had recently done a sit-in in the house, because the house doesn't have a filibuster, so they did a sit in about gun violence. And, you know, so they're talking about the issue and this and that, and it's like, well, wait a minute, if you look at the first page, or the main page of the DNCs website, gun violence isn't on there. It doesn't have a dedicated thing. How can you make a video like this? Talking about gun violence, and it's not one of your core tenets of your party's platform? So I got them the changes. And not only was it on the main page, they put a dedicated website for it, talking about gun violence prevention. But since then — obviously this is not me, or not all me — since then, you would be hard pressed to find a candidate at least at that level who wasn't talking about guns violence prevention. Obama had done it, Hillary did it, Kamala, Joe, all of the Democratic candidates in 2018 and ‘19 were talking about it. Mayor Bloomberg ran on a platform of gun violence prevention. And it just became like this groundswell of effort of people participating in the movement. You know, the Wear Orange Day and weekend turned into a week, and we have more and more people participating in that. And it's created a groundswell.

But back when I ran for Congress, I mean, I was one of the few that were doing it. In fact, that year, Everytown only endorsed one candidate that year. That was Hillary Clinton. That's it. But since then, they participate in races up and down the ballot, which is a great thing. But back then, when it wasn't fashionable to run for office, I believed in what I stood for. I'm glad I did it, I don't regret it, but there are some things I wish, like with everything, I wish I would have known then what I know now, and I would've done a whole host of things differently. My god, yes, way different.

Khary Penebaker

Caitlin: In some ways, I believe that running as the serious underdog gives you an advantage because you have nothing to fear, right? There's no punches worth pulling, and you do get to hold people's feet to the fire, which in my own personal experience, I ran for state representative, and that was terribly satisfying. And so while you lose on election night, right, which is always very disappointing, you didn't lose. You're responsible for making a lot of that change and for showing other individuals, hey, maybe I can run too, whether it's for town council or for president, and everything in between. So I just share that with you. So that sometimes if you're having a bummed out moment about, Oh, I really wish I won in 2016, like you did win. You didn't like get the ultimate win, right? But you had lots of wins along the way, and those are still paying out dividends today. So that's my pep talk.

Khary: If you really think about it like if you look again before you know 2012, ‘13, 14, when the gun violence prevention movement was still there like with Brady and some of the others like the 1 Million Mom March and all that, it wasn't as boisterous as it has become, and it was really elevated by Everytown and Moms Demand, and even that changed. And it had to start with someone willing to do the hard work, the work that the Brady campaign had done really didn't lay the groundwork. Maybe that was probably more from a policy perspective, not so much like the common person advocacy side that Moms kind of brought on that real groundswell of local folks getting involved.

But running for politics, I think, is the same thing, because before 2016, people just, regular folks just weren't doing it. It just was not the thing. But you have to have people who are wanting to start, whether it's AOC or Lucy McBath, regular people running for office and then winning and having conversations with people that you may not have thought were going to be had at all. I mean, do you think, can you just imagine that you have a flight attendant whose son was shot and killed become a three-time serving member of the house? It just wasn't something you would normally get. Lucy's not rich, she doesn't come from a wealthy family, she didn't self-fund her campaigns. She ran on a platform of common sense gun reform and won. She beat someone who had, well, Republicans who had the seat since I think 1984. It is astounding what we can do when we decide, we've simply had enough of the common narrative and we wanna have a conversation about what really should happen. And people like Lucy have shown us the way. And I believe, and if we have more people who are willing to do that — and you're seeing more people do that now — I think that the tide will turn.

We may be in a dark place right now politically, but — I think there was a bit that Dave Chappelle did a while back where he talked about how when Emmett Till was brutally murdered, it was later found out that the woman who accused him of whistling at her recanted and said she lied. But that lie is what kicked off the civil rights movement. Maybe this Trump thing is what's going to really inspire us to become who we are supposed to be. Whether your issue was gun violence prevention, women's reproductive rights, or anything else, that we can't just sit idly by and hope someone else is going to fix these things for us. This is our country. These are our families that are dying. When you think about gun violence prevention, it's not some numbers, not some statistic that bleeds. I don't sit a spreadsheet of numbers in a chair at Christmas thinking it's my mom, right? There's a human being missing. Those numbers don't bleed like our loved ones do. So if we if we talk about these things from a human perspective, there's no no way we can't win.

Devin: As somebody who will never run for political office myself, it does really like spreadsheets. Yeah, I kind of want to like take a moment and turn to like disinformation, the role that's played. And one area that strikes me is going through how the gun violence prevention movement has changed over the years, and what you're mentioning that like, from before 2016 it really wasn't something that you'd run on. And I think a large part to that is that there was back in the year 2000 after Columbine a substantial movement where Donna Dees and others were able to do the Million Mom March and there was momentum there. And then the 2000 election happened, and Democrat strategists were looking for something to explain why Bush beat Gore, and they pointed at the NRA and gun violence. And then it became verboten to run on gun violence, and that wasn't a spell that was broken until like 2012, 2016.

And like, analyzes going back, like, look at that — no, that was a complete fiction that gun violence prevention cost Gore the election. But it was a powerful myth that held, and I deeply appreciate your efforts like through the DCCC to get gun violence elevated as like a major issue to discuss. And one of the things that I've been somewhat frustrated by — like politically but also in gun violence prevention -- is the lack of focus on disinformation, and the falsehoods particularly around guns that permeate society. And like one example of this was in the past election — and I've talked about this in articles and on this podcast before, but to not rant too far — basically when you asked voters whether they thought that violence, particularly gun violence, was going up or down under Biden, those who answered correctly — that it was going down — overwhelmingly voted for Kamala Harris; whereas those who believed the falsehood, which was deliberately spread by various actors connected to the gun lobby, it was the reverse. And yet there was very little systematic effort to counter that disinformation and those falsehoods.

And even in the gun violence prevention space, like the NRA and gun lobby more broadly has had a 50-year headstart on providing this false narrative that guns make people safer to where a majority of Americans believe that. And those who don't go and like actually research the topic and such might just purchase a gun and then tragedy happens before like they realize that like, Oh, that actually wasn't true. And so to kind of wrap that tangential rant up, I'm curious what sort of impact disinformation, encountering disinformation has had in your advocacy and political career. And what are some of the most common elements of disinformation that you encounter?

Khary: Sure. So the narrative that you're talking about from '24, having, you know, been a part of that campaign to get Kamala elected was pervasive, right? I mean, you heard it a lot about how the crime statistics were increasing under Biden when in reality that weren't — and it seemed like no matter what we did, no matter how fervent we fought, and how many statistics we showed that people just wanted to believe that it was the opposite. I mean, that adage is true, that the lie gets across the world before the truth gets its pants on. It couldn't have been more true in '24 for a variety of issues than any of the time before that. And it is staggering to think, as a reasonable person, how do you combat that level of disinformation and really dishonest people, or people who are just intellectually dishonest or lazy. They want to believe that crime is bad to justify voting for someone who was a terrible human being.

It's hard to reconcile with the Trump phenomenon, because it is — I mean, this is something that is rather an anomaly to a degree. So because it's not a traditional politician or someone who is at least steeped in politics, it's hard to combat someone who is a phenomenal marketer. No different than the NRA, where they are able to market fear better than anybody else can, and Trump capitalized on them. But there are people who traffic in that level of disinformation in the GVP space as a career. That's all they do. And it takes people who are willing to share their story, not as an advocate, but as either a survivor of gun violence itself, or an attack yourself, someone who has been shot. There are a number of us who have been — whether it's at Capitol Hill, like Sandy has been a few times, or some of the other folks like you can name any of them really — who have been through it. But when you really put a face with the number, and you can humanize it, it becomes more, I don't wanna say acceptable, but believable that this is a real thing. And unfortunately, there are people who look at the issue as something that just doesn't impact them because it hasn't yet. And that's unfortunate, too, because we are trying to be proactive and not reactive.

But the issue itself is one that because of how the gun lobby and Republicans talk, it creates a difficult space for us to have conversations in a real, blatantly honest way. So because of the lies and misinformation that they use, we have to be more careful and intentional with our words. So we don't talk about gun bans. We will talk about like preventing the future sale of X, Y, and Z type of thing, or talking about background checks, or like we talk about things in terms of policy, and we don t really use the same type of buzzwords that the opposition uses because it's the trap. Like you don't wanna talk about a gun ban or a gun buyback program. We have to talk about things in a different way, hoping to get to the same result of reducing access. That's really what this is about, reducing access, not because we wanna be gun-free, but because we want to reduce the access to those who should not have access to them. And the campaign, like this onslaught, whether it's by the NRA or the Gun Owners of America, or you name it, I think solely because they have a financial interest in doing so, will lie until the cows come home. They have zero interest in telling the truth, and they do it more, and do it better than we tell the truth.

We need to get more people who are having these conversations in a broader spectrum, in a more public space that are willing to lose. You consider what happened in Australia, regardless of the policy, but you consider after 1996 they had their mass shooting, the conservative government decided we're going to change the policy so we don't have this happen again. Again, ignore the policy. That's not a policy that I necessarily agree with for America. But you had a conservative government decide we want to protect our citizens' lives more than we want protect the guns. They've only had one mass shooting since then in 30-some odd years, something like that. But it was a conservative government that did that, and they risked their jobs to do so. And they all lost by the way. But you ask them again now, they'll tell you we don't regret anything that we did because we saved people's lives. That kind of sentiment isn't present in American politics. Where people are willing to lose based on an issue, like, you know what i'm willing to you know go to the mat on this one. We just don't have that, and I think when we get politicians who are like you know what this I can lose my seat, but i'm not going to lose this fight. If we had something like that it wouldn't matter how much the NRA lied, because at that point it's just it's a matter of we're just going to win, we don't accpt losing.

Devin: And the gun lobby's firehose of falsehood, as we've coined it, it is definitely challenging to counter the disinformation at both a personal and organizational level, but it is possible. And one of the crucial things is calling out the specific falsehoods and really educating people, because when I've engaged in conversations with people who aren't in the gun violence prevention space and are typically politically conservative, like the information just isn't seeping through because the firehose of falsehood has just been so overwhelming; and to counter a firehose a falsehood, you need a firehose of truth as well as inoculation campaigns that are proactive. Like you were mentioning to where basically you're pre-bunking the disinformation they're likely to encounter, and then having media outlets and others being willing to cover it.

And like in the most recent campaign, the disinformation narrative on crime rates came directly from John Lott. And basically none of the fact checkers or media organizations, like while they would touch on the numbers, they didn't delve actually into who is responsible for these numbers. I mean, it's basically like having Andrew Wakefield give a dissertation on vaccines and that being adopted by a campaign. It's, it was just a weird moment of silence on something and seeing, like, lots of data getting pushed out by Elon Musk, the richest man in the world, adopted as main Trump campaign talking points, and there just not being a strategic effort, at least it felt like, to hey here's this falsehood, here's why it's false, and here to tell how it's being spread, and they're lying to you like massively on this.

Khary: And that's one thing I think we need to start calling out the lies themselves as lies, not just misinformation or half-truths or anything like that. This is a flat-out lie. We need to be more forceful on our side. I also think we have a difficulty with politicians who don't have this issue as their primary issue. When they go to talk about it, they often use the wrong terminology and then get themselves in trouble, where their words are then used against them because they don't know the right words to use because words actually matter. Our opposition doesn't have to look at things from an intentional perspective and use correct words, they can say anything they want because they're already lying. We are the truth-tellers, so we have to use the right words.

And oftentimes people don't take the time to study the issue to know what the right thing to say or not say. And that's also a detriment to our effort because now you gotta clean up their mess. Like I want people to be educated on the issue and not use it as just the cause of the day. These issues matter. I understand, you know, again, having seen how the sausage is made, that politicians have a wide variety of issues that they are advocating for and legislating against. I get it. But when it comes to life and death issues like gun violence prevention, you have to know what you're talking about.

Caitlin: Khary, what do you think your mom would say today if she could see the positive impact that you've had on so many people?

Khary: I often wonder what that would be like. [But the real reason it's hard] for me to answer from at least a purely honest perspective is because I don't know what my mom's voice sounds like. I was only like 19-months old, something like that, when she completed suicide with that gun. So I don't know what it would be like to have my mom say anything to me. And after, I think it was maybe 2015 or so, at one of the Sandy Hook vigils in D.C. I gave a speech and Valerie Jarrett was in the audience. And I didn't know CNN was also there recording. I had no idea. I didn’t even see cameras. It didn't matter. Obama could have been there, it wouldn't have mattered. I knew what I wanted to say. And ultimately what I was saying is that I don't know what my mother's voice sounds like. I don't know what it sounds like to have my own mother tell me that she loves me, because she had easy access to a gun. And at the end of the speech, and you know we're all hugging and everybody's crying and stuff, Valerie Jarrett comes up to me and she says, your mother would be so proud. And CNN ran that moment. Again, I had no idea it happened. Someone sent it to me. I didn't even see it.

So I would like to believe that she would say that she was proud, but I would think that if I was able to actually talk to my mom, that I wouldn't be in this space. That I, at least from the perspective that I have to be in it — as a gun violence survivor not having his mom — maybe I would just be an advocate, someone wanting to save lives as a decent human being and have my mom be my champion, because I don't want people to suffer and struggle. But given that I have to do this as someone who has had to live it, I don't know what she'd say. I mean, I can't imagine she would not be proud of me, but I would much rather have my mom be here than be proud.

So I would chew off my left arm just to be able to sit there with her and just tell her, you know, struggle through one more day. Find out what I'm gonna be as an adult, get a chance to meet your grandkids. I want to say like normal stuff to her, I want to like have my mom teach me how to brush my teeth or tie my shoes, or be there when I roll my bike the first time, or be there to watch me get a scholarship to college. Basic things. You know, have her be there like when I made mistakes or when I had successes or, you know, when I just have a good day or a bad day. I can just call my mom and just say basic random things. Have a regular argument with my mom. I can't do that. I can't do that because my mom had easy access to a gun when depression was lying to her making her believe that my world will be better off without her.

Caitlin: I hope this doesn't come off as patronizing, but as a mom, I will echo Valerie's words. And your mom absolutely would be proud of you no matter what you did, right? That's our job as moms. But especially now, seeing how much of your time and energy and effort and the sleepless nights I'm sure that you've had to put forth all of this, to the gun violence prevention movement and to other movements to make people's lives better.

Khary: Yeah, I appreciate that. Thank you.

Caitlin: I don't know. This is like time 70 that I've cried on our podcast here. So it's fine. Everybody comes to expect it. Do you have any final thoughts to leave us with, or anything that you would like to share before we wrap up?

Khary: Yeah, I mean, I think if there are people who are either facing the tragedy of gun violence themselves, having lived through it, whether you are the victim of it directly or you had a loved one deal with it, I encourage you to get help to talk to people, to talk about your story, and don't let it own you. That's the first mistake I made through the majority of my adult life, allowing this tragedy to control me to a point where I thought that my kid's world will be better off without me. And I had to learn through a lot of dark moments, a lot of hard work that is the furthest thing from the truth. But it took me being at my ultimate low to at least admit that I needed help. I think far too few people in our country, in our world, get the help that they need, and especially men who are societally taught that we are strong and it's not manly to be emotional or to struggle. It takes courage to ask for help, and you are no less of a man or human if you need help. The world is a better place with you in it, and I hope people take the time to appreciate themselves, because you can't take care of others unless you take care yourself first. But you absolutely matter. There are people, I'm sure, either listening or watching, who may have been or may be in their absolute worst, but I promise you, there's someone who wants you to be here. I promise.

Caitlin: Absolutely. Thank you again so much for being here and sharing all of these incredible things that you've done with us, and sharing so much about your own personal story. And we look forward to seeing all that you continue to do in the future. And anytime you want to jump on here and give us an update or talk about a project you're working on or an organization that you partner with, just know where to find us, just let us know and we'd love to chat again.

Khary: And it was very good seeing you two after all this time.

Caitlin: Yes, a pandemic will do that, right? It will create some space between individuals.

Devin: What do you mean it's been six years?

Caitlin: Thank you so much again.

Devin: Yeah, thanks for having me. Talk to you later.

Photos courtesy of Khary Penebaker